|

BHASE n°10

(octobre-novembre 2014)

|

AVERTISSEMENT

|

Cette page est une simple

reversion automatique et inélégante au format html

d’un numéro du BHASE (Bulletin Historique et Archéologique du Sud-Essonne),

pour la commodité de certains internautes et usagers du Corpus Étampois.

|

|

La version authentique, originale et officielle de ce

numéro du BHASE est au format pdf

et vous pouvez la télécharger à l’adresse suivante:

|

http://www.corpusetampois.com/bhase010w.pdf

|

|

|

BHASE

n°10 (oct.-nov. 2014)

|

Foreword

|

Préface

|

3-4

|

|

1120-1598

ANCESTORS 6-66

|

|

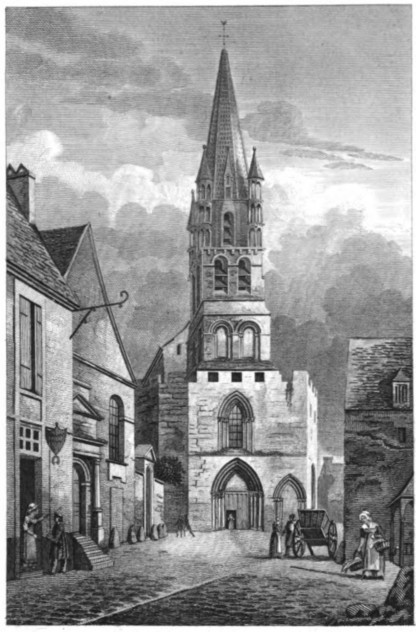

1120.

Theobald of Etampes at Oxford 6-16

|

|

1536-1598

The Duchesses of Étampes in Poetry 17-33

|

|

1575

Pierre Baron at Cambridge 34-66

|

|

1787-1909

TWELVE VISITORS 67-140

|

|

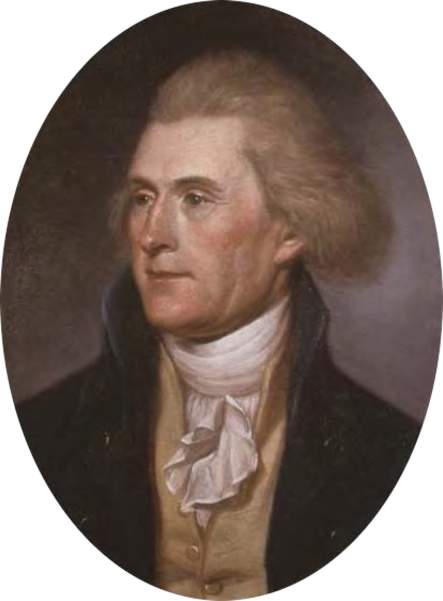

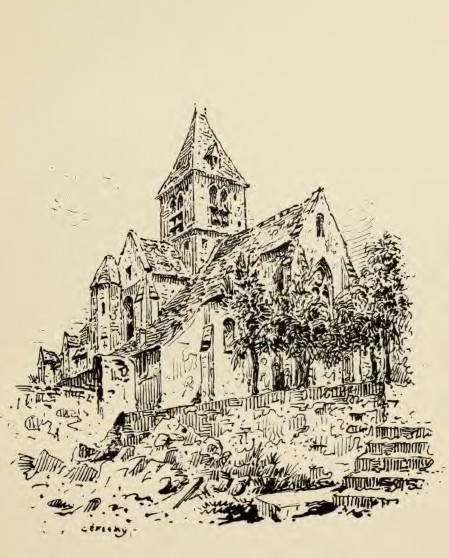

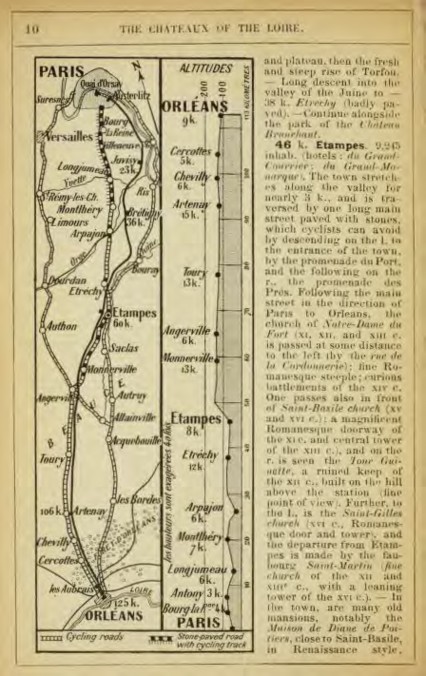

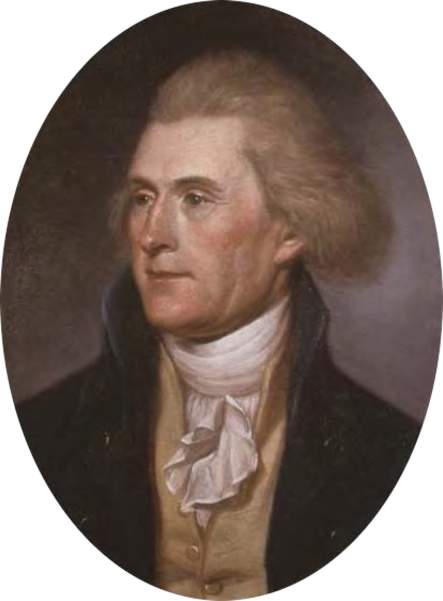

1787

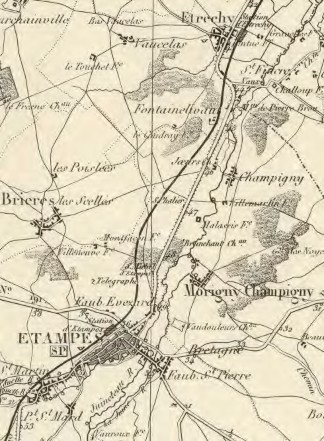

Thomas Jefferson 68-69

|

|

1801

Heinrich Friedrich Link 70-73

|

|

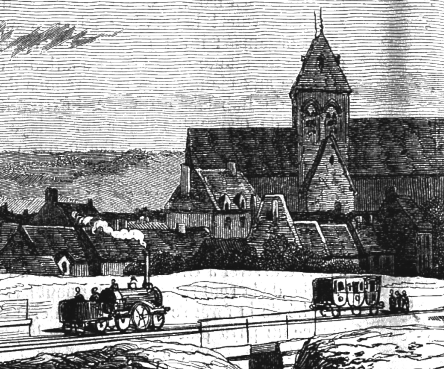

1829

Heinrich Reichard 74-77

|

|

1838

Richard Brookes

78

|

|

1843

John Murray 79-87

|

|

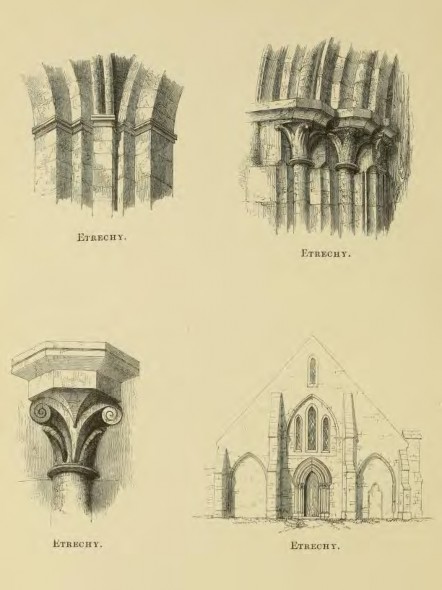

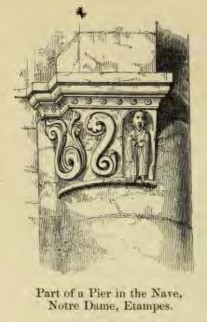

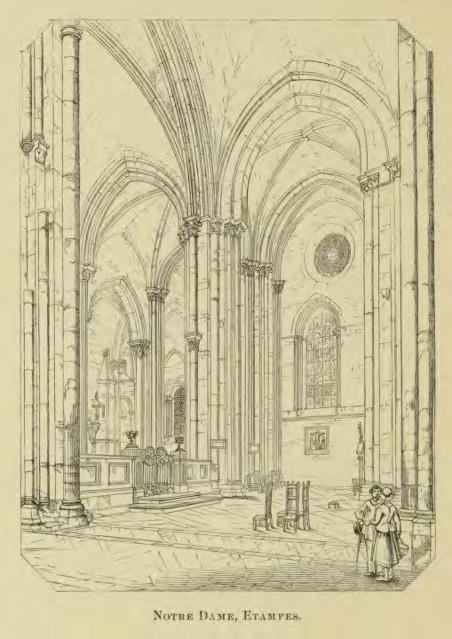

1854

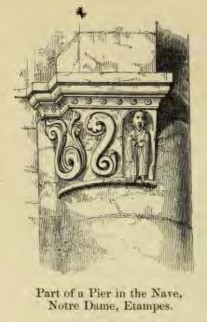

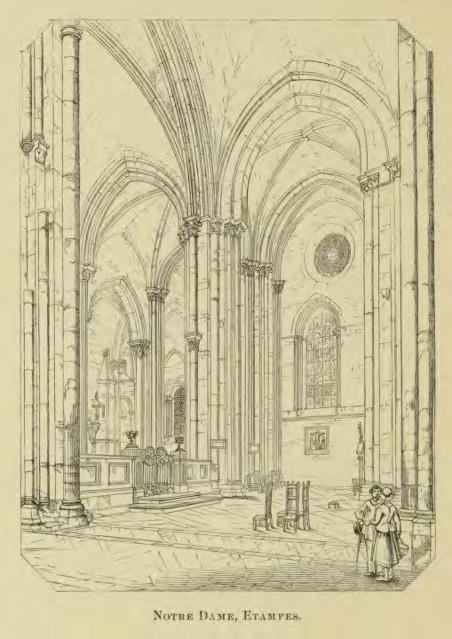

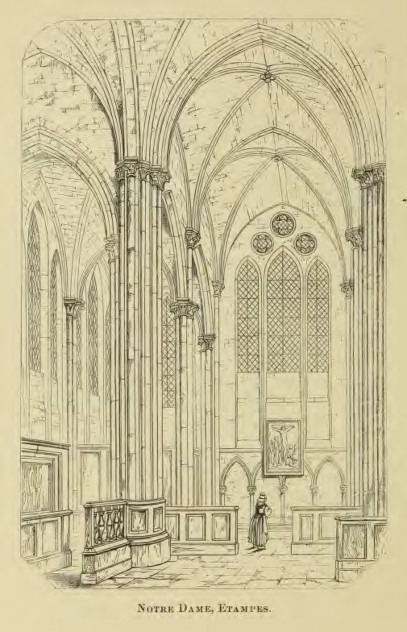

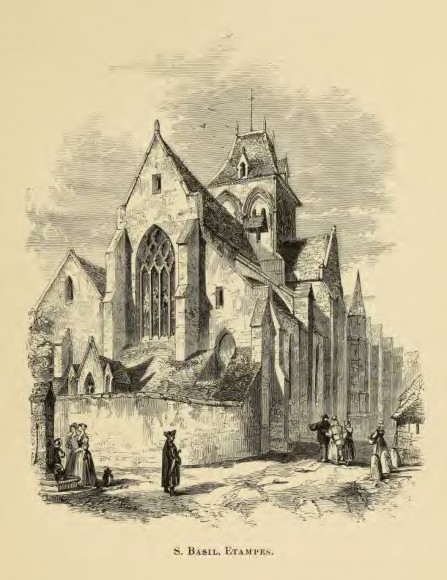

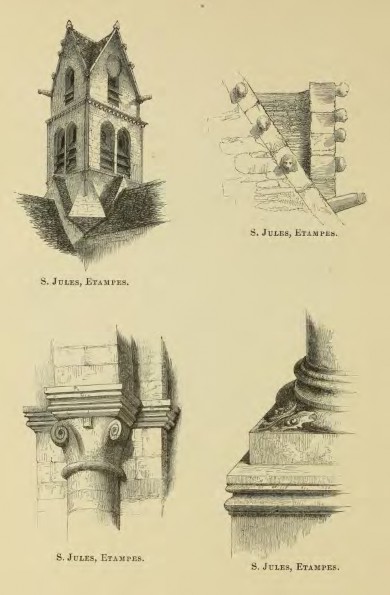

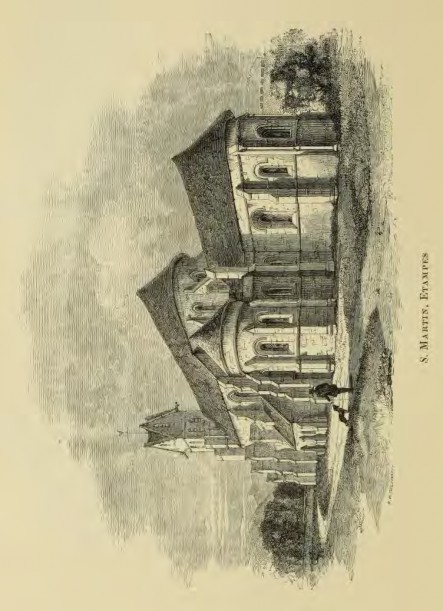

John Louis Petit & Ph. H. Delamotte 88-105

|

|

1866

Charles Knight 106-109

|

|

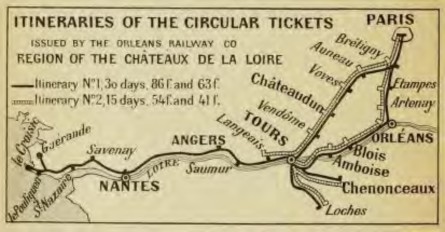

1873

George Bradshaw 110-112

|

|

1906

Edith Wharton 113-116

|

|

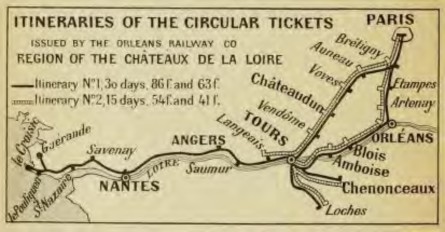

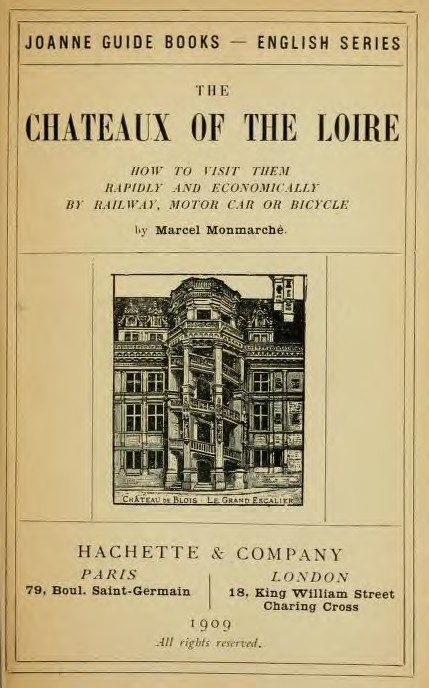

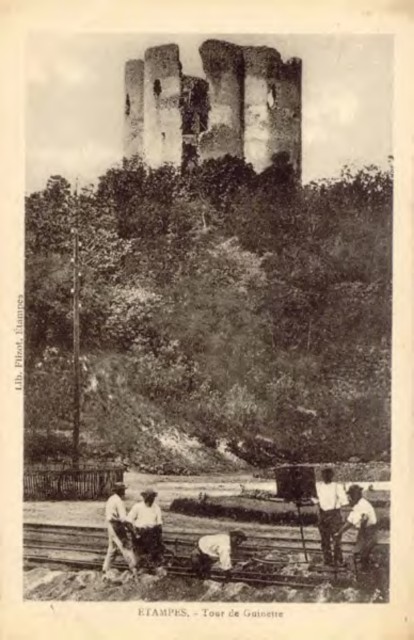

1909

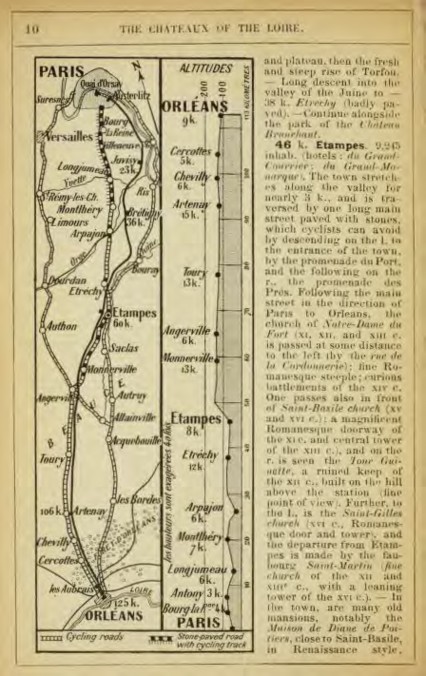

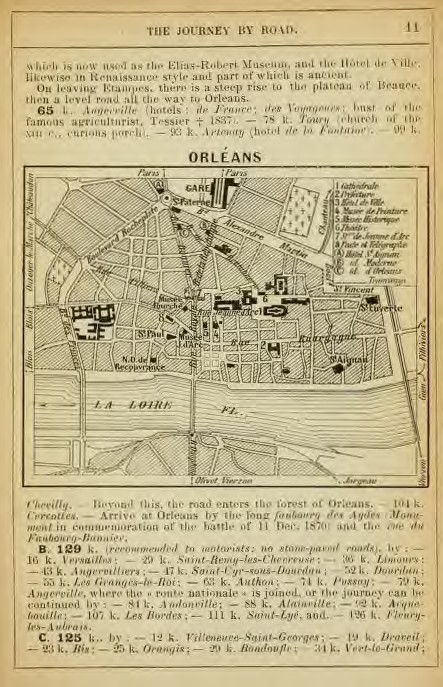

Marcel Monmarché 117-123

|

|

1908

T. E. Lawrence of Arabia 124-140

|

|

1910-1913

THREE FLYING WOMEN 142-158

|

|

1910

Mlle Abukaia 142-145

|

|

1911

Denise Moore 146-152

|

|

1912

Suzanne Bernard 152-158

|

|

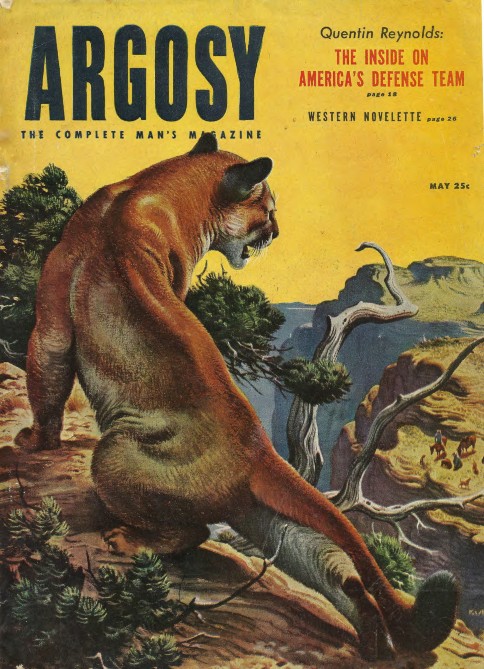

1913-1951

ADVENTURES 160-293

|

|

1913

Captain Clive Mellor : The Airman 160-254

|

|

1913

Tarzan fights duel near Etampes 255-268

|

|

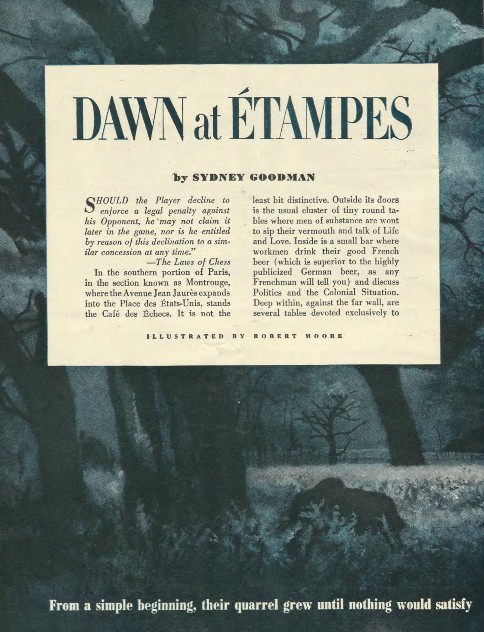

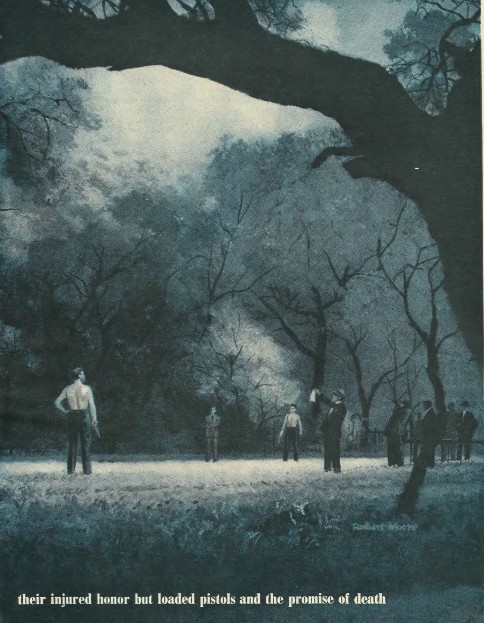

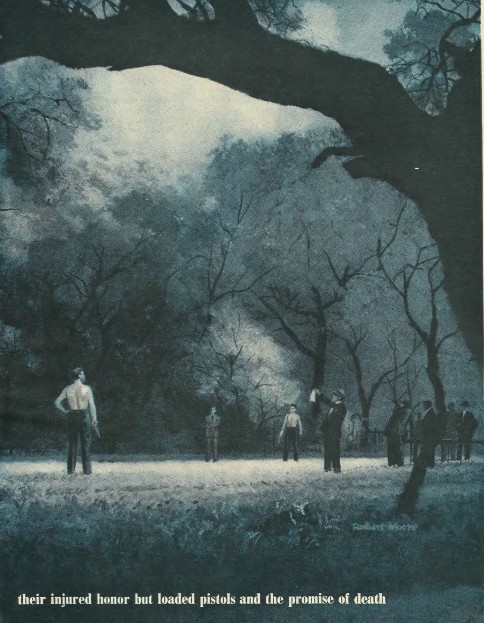

1951

Dawn at Etampes. A short novel by 269-293

|

(Fly

training at Etampes)

Sidney

Goodman

ISSN

2272-0685

Publication

du Corpus Étampois

Directeur

de publication : Bernard Gineste 12 rue des Glycines, 91150 Étampes redaction@corpusetampois.com

BHASE

10

Bulletin

historique et archéologique du Sud-Essonne

Publié

par le Corpus Étampois

octobre-novembre

2014

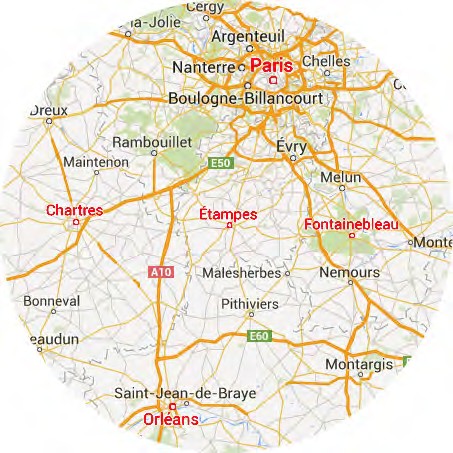

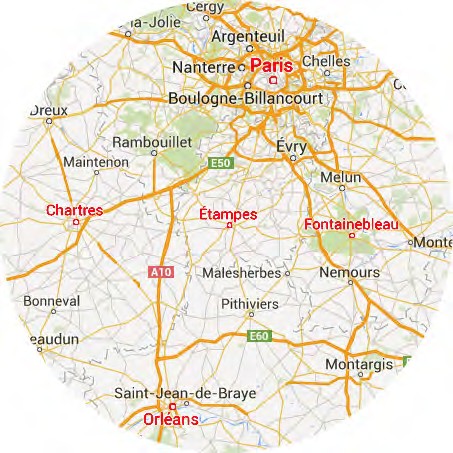

Foreword

Do you

know Étampes ? Well, you don’t ? What a pity. It is nice, old and charming

royal town sixty kilometers south of Paris.

From

Étampes came to England Theobald, where he founded the Oxford University.

From Étampes too came in the Cambridge University another great professor

named Peter Baro.

So precious

was Étampes that three kings of France gave this town to their mistress as

a Duchy : Francis I to Anne de Pisseleu ; Henri II to Diane de

Poitiers ; Henri IV to Gabrielle d’Estrées, who all three were

adressed nice poems ; some of them were translated into English by Luisa

Costello.

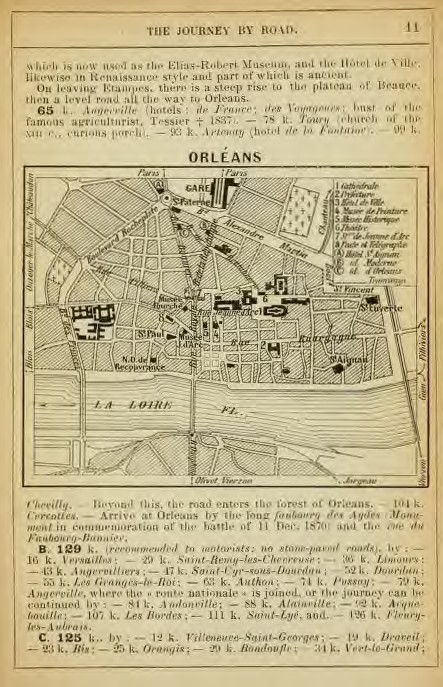

From 1787

to 1909 Étampes was visited by numerous people. So we give here several touristical

notices, by H. F. Link, Heinrich Reichard, Richard

Brookes, John Murray, Charles Knight, George Bradshaw

and Marcel Monmarché.

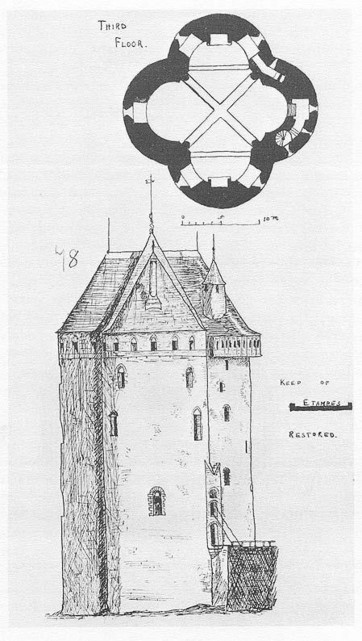

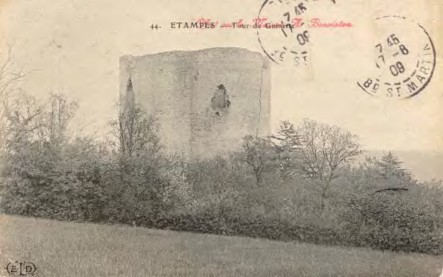

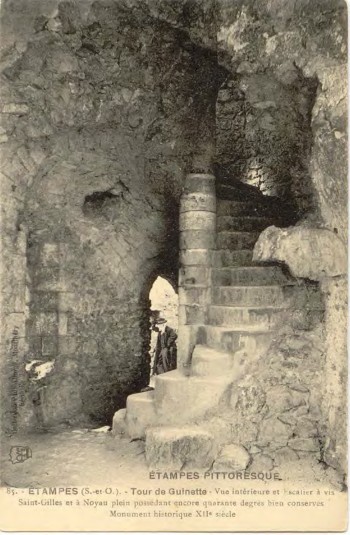

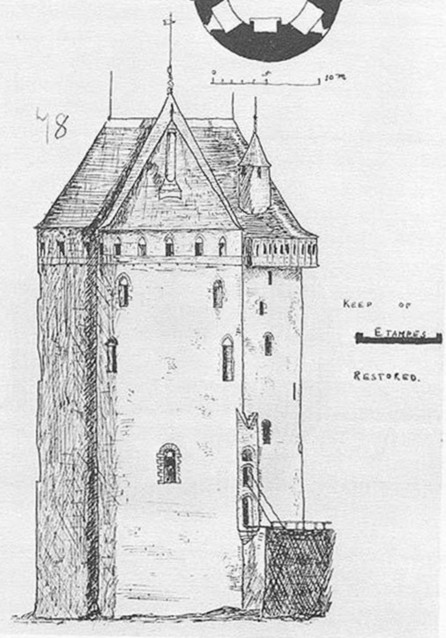

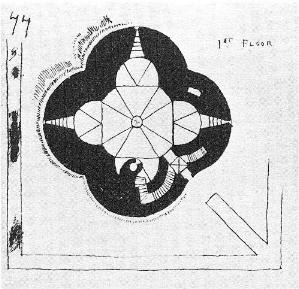

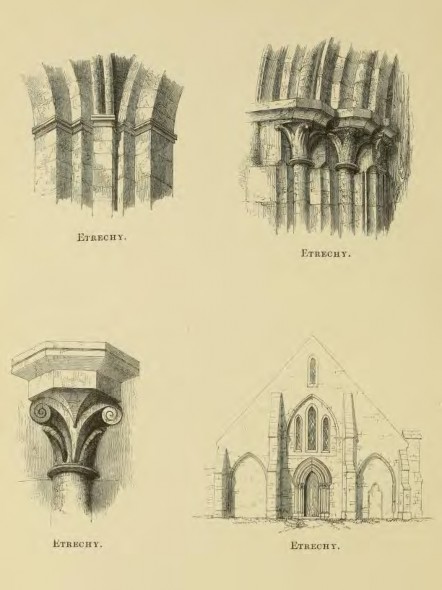

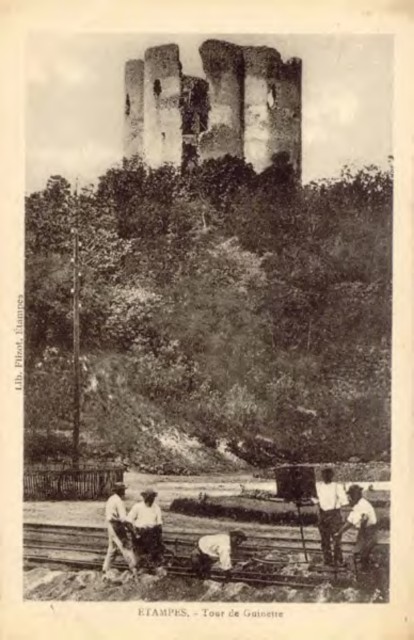

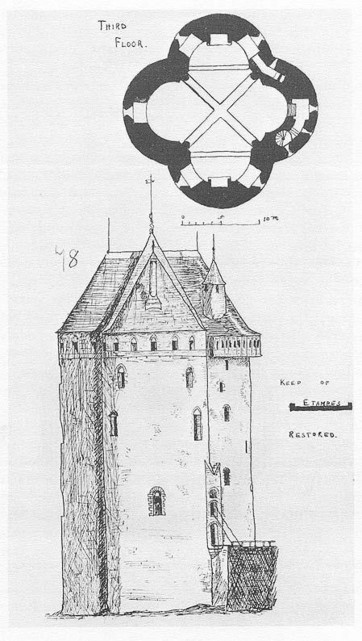

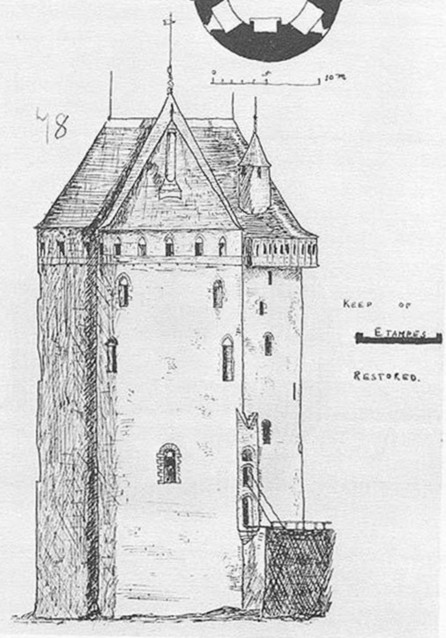

More

interesting are the personal impressions and descriptions by some famous

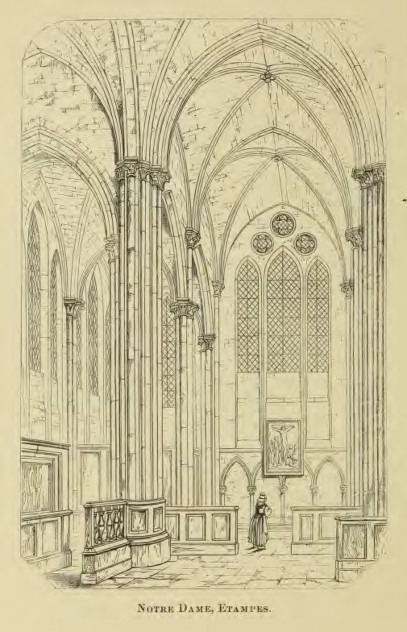

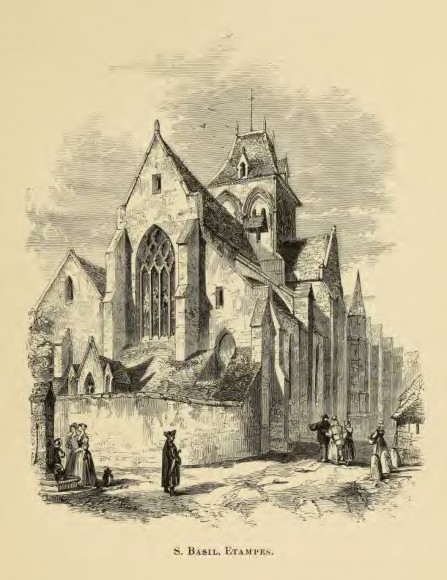

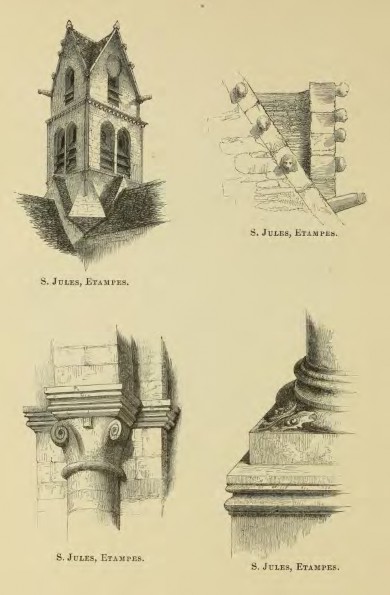

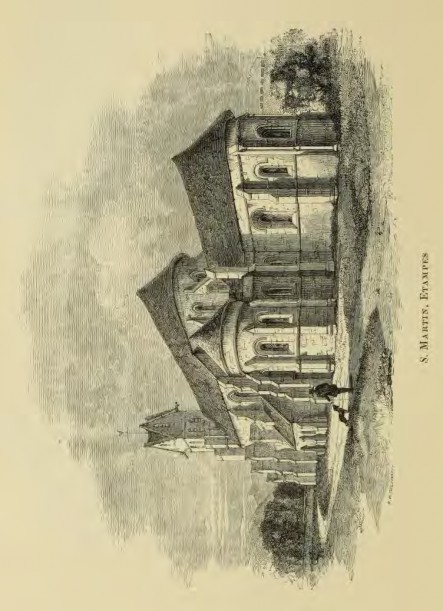

people as Thomas Jefferson (1787), John Louis Petit and Philip

Henry Delamotte, with some very interesting archeological drawings (1854),

Edith Wharton (1906) and T. E. Lawrence, later said of Arabia,

and then

studying

the Tower of Étampes as a specimen of military archeology (1908).

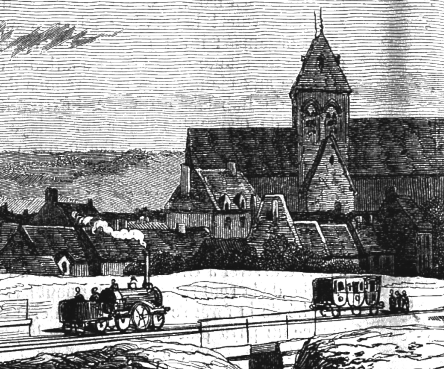

From

1909 to 1913 came the glorious Era of Aviation. In 1910 took place a ridiculous

conflict between the Mayor of Étampes and a flying lady named Mlle Abukaia,

conflict which was talk about from New Zealand to California. During 1911

died at Étampes the first woman victim of aviation, Denise Moore ;

and, the following year, the second woman to die victim of aviation,

dyed once more in Étampes, i. e. Suzanne Bernard. During 1913 was

published by Captain Clive Mellor the first description in the world

of a school of aviation, that of Étampes, where he learned to fly.

The

same year, according to Edgar Rice Burroughs, in the second volume of the

Adventures of Tarzan, lord of the Apes, Tarzan fought duel near Étampes.

Finally

another American writer, Sidney Goodman, probably inspirated by this

late novel, wrote he too a short novel about another duel near Étampes, published

in 1951 , Dawn at Étampes.

So, enjoy

reading, please !

Bernard Gineste

Theobald

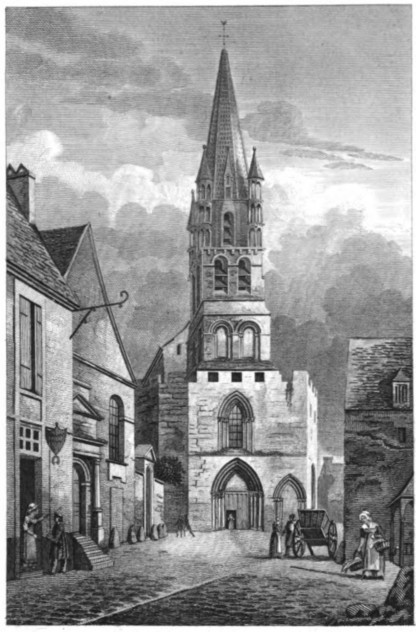

of Étampes (postcard after a painting by Bowley, 1907)

12th Century XIIe siècle

Theobaldus

Stampensis

Theobald

of Étampes

Thibaud

d’Étampes

Forerunner

of the Oxford University

by Gaëtan

Poix for Wikipedia

after

the paper : « Thibaud d’Étampes » by Bernard Gineste (2009)

Thibaud

d’Étampes

Thibaud

d’Etampes, en latin Theobaldus Stampensis (né vers 1080 à Étampes, mort après

1120 sans doute à Oxford) est un écolâtre et théologien du début du XIIe

siècle, traditionaliste et à ce titre hostile au célibat des prêtres. C’est

aussi le premier écolâtre connu d’Oxford où il est considéré sinon comme

le fondateur, au moins comme le précurseur de l’université.

Biographie

Les

grandes étapes de la vie de Thibaud d’Étampes n’ont été reconstituées qu’en

20091. Chanoine et fils de chanoine, il a grandi à Étampes

au milieu de nombreux prêtres mariés, à l’époque où se met en place la Réforme

grégorienne qui impose le célibat des prêtres. Probablement formé à l’école

cathédrale

de Chartres,

il devient, comme l’a montré Bernard Gineste, écolâtre de Saint-Martin d’Étampes

et précepteur du jeune vicomte de Chartres Hugues III du Puiset. À cette

époque le roi Philippe Ier de France, et surtout son fils aîné, le futur

Louis VI le Gros reprennent pied à Étampes, ville jusqu’alors contrôlée par

les vicomtes du Puiset. Simultanément le roi s’appuie sur les moines de Morigny

qu’il favorise au détriment des chanoines mariés d’Étampes.

1 Bernard

Gineste, « Thibaud d’Étampes », Cahiers d’Étampes-Histoire

10

(2009), pp. 43-58.

Theobald

of d’Étampes

Theobald

of Étampes (Latin : Theobaldus Stampensis, French : Thibaud or

Thibault d’Étampes; born before 1080, died after 1120) was a medieval

schoolmaster and theologian hostile to priestly celibacy. He is the first

scholar known to have lectured at Oxford and is considered a forerunner of

Oxford University.

Biography

Theobald’s

biography has been reconstructed by Bernard Gineste. Theobald was a canon

and the son of a canon from Étampes. As a child he knew many married priests

around Étampes, at a time when the Gregorian reform was requiring celibacy

of priests. He was probably educated in the Chartres Cathedral School, and

became master (in latin scholaster) of the school of the parish of

Saint-Martin at Étampes and a private tutor to the young viscount of Chartres,

Hugh III of Le Puiset. After King Philip I of France annexed Étampes to the

royal domain he began to favour the monks of Morigny over the local priests.

In 1113, after Hugh of Le Puiset was captured and imprisoned by royal forces,

Theobald left Étampes for the Duchy of Normandy.

C’est

dans ces circonstances, alors que son jeune élève, rebelle à l’autorité royale,

vient d’être capturé et emprisonné pour la deuxième fois, que Thibaud quitte

en 1113 le domaine royal pour les terres anglo-normandes d’Henri Beauclerc.

Il fuit d’une part l’hostilité du roi Louis VI, et d’autre part une terre

où s’impose de plus en plus, par la force, le célibat des prêtres, et le

contrôle des paroisses par les moines.

On le

trouve d’abord écolâtre à Caen, où il semble envisager de passer de là au

Danemark, mais finalement c’est en Angleterre qu’il va s’installer, précisément

à Oxford. Il y donne son enseignement devant un public de 60 à 100 clercs

: c’est le premier noyau de l’ultérieure université d’Oxford.

Œuvre

et pensée

On a

conservé six Lettres de Thibaud d’Étampes. Deux sont écrites de Caen. La

première est une lettre de consolation écrite à un certain Philippe, qui

avait commis un écart sexuel non déterminé et subi des brimades en conséquence

; Thibaud développe l’idée que les fautes de ce genre ne sont pas les plus

graves, et que l’orgueil est un péché bien plus dangereux ; il donne de plus

à entendre clairement que ceux qui font profession de chasteté tombent souvent

dans la pédérastie. La deuxième lettre est adressée à une reine Marguerite

qu’on croyait jusqu’alors être sainte Marguerite d’Écosse, morte en

1093,

mais Gineste a montré qu’il s’agit de Margrete Fredkulla, reine de Danemark,

encore vivante en 11162 ; il

remercie la reine d’une libéralité en faveur de l’abbaye aux Hommes de Caen

et semble lui faire des offres de service.

2 Cette

confusion, débrouillée par Gineste, avait jusqu’à présent empêché toute reconstitution

de la trajectoire professionnelle et intellectuelle de Thibaud d’Étampes.

There

he became schoolmaster at Caen and planned to leave France for Denmark, but

in the end he crossed the Channel to England, where the Duke of Normandy,

Henry Beauclerc, was king. At Oxford he gave public lectures to audiences

of between 60 and 100 clerics.

Work and

thinking

Six letters

of Theobald of Étampes has been preserved.

Two

are written in Caen. The first is a letter written to a certain Philipp,

who had committed an undetermined sexual deviation and sustained harassment

accordingly ; consoling him Theobald develops the idea that the faults of

this kind are not the most serious, and that pride is a far more dangerous

sin; he very clearly suggests that those who make profession of chastity

often fall into pedophilia.

The

second letter is sent to a Queen Margarita, thought until recently to be

Saint Margaret of Scotland, died in 1093, but Gineste has shown she is Margaret

Fredkulla, Queen of Denmark, still alive in 1116.3

He thanked the Queen of liberality of the Abbey of

Saint-Étienne of Caen and seems to make service offerings.

3 This error

explains the misdating of the whole works of Theobald until the recent paper

by Gineste.

Quatre

sont écrites d’Oxford. Il paraît impossible de leur donner un ordre chronologique.

L’une est adressée à Farrizio, abbé d’Abingdon, pour se défendre d’une accusation

d’hérésie. Il s’en défend et démontre que son enseignement est orthodoxe

: les enfants morts sans être baptisés vont bien en enfer. La deuxième lettre

est adressée à l’évêque de Lincoln (Royaume-Uni) ; c’est la plus longue et

il y est démontré par l’autorité de l’Écriture et des Pères de l’Église que

même le plus grand des pécheurs peut accéder au salut s’il se repent à sa

dernière heure. La troisième est adressée à l’hérétique Roscelin de Compiègne

; cependant la doctrine propre de Roscelin ne l’intéresse pas : il lui reproche

seulement d’avoir mal parlé des fils de prêtres, et défend ces derniers en

rappelant que saint Jean Baptiste en était un ; il exprime aussi une opinion

extrêmement rare à ce sujet : la Vierge Marie également aurait été fille

de prêtre. La dernière des quatre lettres d’Oxford s’en prend aux moines

et leur refuse le droit de prendre la place des clercs, de percevoir les

dîmes et de revêtir les charges et les dignités qui étaient jusqu’alors le

monopole des clercs et des chanoines.

Cette

dernière lettre, assez brève, a été l’objet d’une réponse interminable d’un

moine anonyme, en partie versifiée4, qui s’en prend vivement

aux clercs et aux chanoines de son temps, et fait l’éloge en retour des moines,

parés de toutes les vertus.

4 Éditée

par Raymonde de Foreville et dom Jean Leclerc, in Studia Anselmania 41

(1957), pp. 8-118.

Four

are written from Oxford. It seems impossible to give them a chronological

order. One is addressed to Faritius, Abbot of Abingdon, to defend himself

from a charge of heresy. He has defended and shows that his teaching is Orthodox:

dead children who have not been baptized go to hell. The second letter is

sent to the Bishop of Lincoln, England; it is the longest and is proving

by the authority of Scripture and the Fathers of the Church that even the

greatest sinners can access the salvation if he repents up to his final hour.

The third is addressed to the heretical Roscellinus of Compiègne. However,

the doctrine of Roscellinus about Trinity does not interest Theobald. He

accuses him of criticizing the sons of priests, and defends them by pointing

out that Saint John the Baptist was one. He also expresses an extremely rare

opinion on this subject: the Virgin Mary was also a daughter of a priest.

The last of these four letters of Oxford deals with the monks and denies

them the right to take the place of the clerics, and to collect tithes and

benefits which were until then the monopoly of the clerics and the canons.

This

last quite short letter has subjected to an anonymous monk an endless answer,

partly written in verses, which strongly supports the clerics and the canons

of the time, and praise in return for the monks, trimmed of all virtues.

Place

dans l’histoire des idées et dans la tradition

Thibaud

d’Étampes n’est pas un auteur majeur, mais c’est l’un ces premiers intellectuels

qui ont frayé la voie à la grande renaissance du XIIe siècle. Les principes

majeurs de son enseignement sont le respect et l’exposition méthodique, autrement

dit raisonnée (rationabiliter), de la doctrine de l’Église.

Sa pensée

doit être resituée dans le grand débat qui agite son temps : pour ou contre

la grande réforme grégorienne en cours ; pour ou contre la prise du pouvoir,

au sein de l’Église, par les moines, à un moment où tous les papes sont d’anciens

moines, et tentent d’imposer par la force leurs conceptions ascétiques à

l’ensemble du clergé.

L’historiographie

oxfordienne y a aussi souvent vu le fondateur de l’université du lieu, et

en 1907 a été composée et jouée une saynète le présentant comme l’introducteur

des lumières à Oxford, en opposition avec les forces de l’obscurantisme

représentées par les moines d’Abingdon. Il s’est, bien entendu, également

attiré la sympathie de l’Église anglicane par son hostilité au célibat des

prêtres, célibat qui a rencontré une grande résistance de fait dans toute

l’Europe du Nord jusqu’à la fin même du Moyen Âge, tandis qu’en France catholique

son œuvre a été progressivement oubliée.

Place

in the history of ideas and traditions

Theobald

of Étampes is not a major author, but is one such early intellectual who

has paved the way to the great 12th century Renaissance. The major principles

of teaching are respect and methodical, in other words reasoned exposure

(in latin rationabiliter) of the Catholic doctrine.

His

thoughts should be seen in the great debate of his time: for or against the

great Gregorian reform; for or against the taking of power within the Church,

by the monks, at a time where all the Popes are former monks and attempt

to impose by force throughout the clergy their ascetic designs.

Also

Oxfordian historiography often saw him as the founder of the University,

and in 1907 was composed and performed a skit presenting him as the introducer

of the enlightenment in Oxford, in opposition to the forces of darkness represented

by the monks of Abingdon.

It of

course also attracted the sympathy of the Anglican Church by his hostility

to the celibacy of the priests, celibacy that met resistance in fact in Northern

Europe until the end of the Middle Ages, while in Catholic France his work

was gradually forgotten.

Bibliographie

– Bibliography

Luc

d’Achery, « Theobaldi Stampensis [Epistolae] », in Veterum Aliquot Scriptorum

qui in Galliae Bibliothecis, maxime Benedictorum, latuerant, Spicilegium:

Tomus tertius, Paris, 1659, pp. 132-145 (réédité par Migne dans sa Patrologia

Latina, vol. 163, col. 759-770).

« Thibaud d’Etampes », in Histoire littéraire de la France

: XIIe siècle. Tome XI, Paris, Nyon, 1757, pp.90-94.

Robert

Bridges, « Theobaldus Stampensis (The Beginnings of the University) », in

The Oxford Historical Pageant, Oxford, Pageant Committee, 1907, pp.

27–34.

Raymonde

Foreville, « L’École de Caen au XIe siècle et les origines normandes de l’Université d’Oxford

», in Mélanges Augustin Fliche, Montpellier, 1952, pp 81–100.

Raymonde

de Foreville and dom Jean Leclerc, « Un débat sur le sacerdoce des moines

au XIIe siècle », in Studia Anselmania 41 (1957), pp. 8-118.

T. H.

Aston, The History of the University of Oxford: The early Oxford schools,

Volume 1: The early Oxford Schools, Oxford University Press, 1985, pp.

5 and 27.

Bernard

Gineste, « Thibaud d’Étampes », in Cahiers d’Étampes-Histoire 10 (2009),

pp. 43–58.

16th Century XVIe siècle

Five

poems translated by Luisa Costello

about

three Duchesses of Etampes

The King

Francis I of France, A.D. 1534, gave to his mistress Anne de Pisseleu the

barony of Etampes, which was made a duchy A.D. 1537.

His son the

King Henri II of France gave it to his own mistress Diane de Poitiers, A.D.

1553.

Later, the

king Henri IV of France also gave thise duchy to his mistress Gabrielle d’Estrée,

A.D. 1598.

Luisa Stuart Costello

Five French

Poems translated about

Three

duchesses of Etampes 1836

Louisa Stuart Costello (1799-1870), poétesse, historienne,

journaliste, peintre et romancière, a longtemps séjourné à Paris et donné

des journaux de voyages et des écrits sur l’histoire de France. On lui doit

notamment un recueil de poèmes français mis en vers anglais, Specimens

of the Early Poetry of France: From the Time of the Troubadours and Trouvères

to the Reign of Henri Quatre.

Nous en extrayons des poèmes rapportés, à tort ou à raison,

à trois duchesses successives d’Étampes, Anne de Pisseleu, Diane de Poitiers

puis Gabrielle d’Estrée.

-

François Ier,

sur Anne de Pisseleu 5

DIZAIN

Est-il

point vrai, ou si je l’ai songé, Qu’il est besoin m’éloigner et distraire

De notre amour et en prendre congé ? Las ! Je le veux ; et si ne le puis

faire.

Que

dis-je ? veux ; c’est du tout le contraire : Faire le puis, et ne puis le

vouloir ;

Car

vous avez là réduit mon vouloir, Que plus tâchez ma liberté me rendre, Plus

empêchez que ne la puisse avoir, En commandant ce que voulez défendre.

5 Texte

donné ici par Maxime de Montrond, Essais historiques sur la ville d’Étampes.

Tome 2, Étampes, Fortin, 1837, p. 69, n. 1.

Francis

I of France – Costello’s translation 6

TO THE

DUCHESS D’ESTAMPES.

Est-il

point vrai.

Is

it a dream, or but too true

That

I should fly you from this hour, To all our fondness bid adieu ? —

Alas

! I would, but want the power. What do I say ! — oh, I am wrong,

The

power, but not the will, have I ; My heart has been a slave so long,

The

more you give it liberty,

The

more a captive at your feet it lies,

When

you command what every glance denies.

6 Louisa Stuart Costello, Specimens of

the Early Poetry of France: From the Time of the Troubadours and Trouvères

to the Reign of Henri Quatre [298 p.], London (Londres), William Pickering,

1835, p. 207.

-

Clément

Marot, sur Anne 7

ÉPIGRAMME

8

Si

jamais fut un paradis en terre, Là où tu es, là est-il sans mentir :

Mais

tel pourroit en toi paradis querre9

Qui

ne pourroit que peines ressentir : Non toutesfoys qu’il s’en doit repentir,

Car heureux est, qui souffre pour tel bien.

Donque

celui que tu aimerois bien, Et qui reçu seroit en si bel estre,

Que

seroit-il ? Certes je n’en sçais rien, Fors qu’il seroit ce que je voudrois

estre.

S’il fut

jamais un paradis sur terre Là où tu es, là est-il, sans mentir,

Mais on

pourrait bien en toi le chercher On arriverait tout juste à le ressentir

: Non toutefois qu’on doive s’en repentir Car heureux est qui souffre pour

tel bien.

Et donc

celui que tu aimerais bien Et qui serait admis à cette situation,

Que serait-il

? Certes je n’en sais rien, Sauf qu’il serait ce que je voudrais être.

7 Pierre

René Auguis, Les poètes françois depuis le XIIe siècle jusqu'à Malherbe,

avec une notice historique et littéraire sur chaque poète. Tome 3, Paris,

Renouard, p. 65.

8 À

mon humble avis il ne s’agit pas ici d’Anne de Pisseleu, mais d’Anne Valençon,

comme dans le fameux Sonnet de neige.

9 Querre, ancien infinitif de quérir, « chercher

».

Clément

Marot – Costello’s translation 10

A ANNE,* POUR ESTRE EN SA GRACE.

Si jamais

fust un paradis en terre, &c.

On

! if on earth a paradise may be,

Where’er

thou art methinks it may be found ; Yet he, who seeks that paradise in thee,

Will

find more pains than pleasures there abound : Yet will he not repent he sought

the prize,

For

he is blest who suffers for those eyes :

What

fate is his, whose truth thy heart shall move, By thee admitted to that heaven

of love ?

I

know not — words his happiness would wrong — His fate is that which I have

sought so long !

*

Anne de Pisseleu, Duchesse d’Etampes11.

10 Louisa Stuart Costello, Specimens…,

p. 200.

11 So Costello.

But that is undoubtedly an error. For never should be so audacious a poet

with such an important person as Anne de Pisseleu. And

there is

an other Anne Marot tell about, i.e. Anne Valençon, e.g. « Anne par jeu me

jeta de la neige… » (B.G.).

-

Clément Marot, sur Diane

CHANSON

POUR DIANE DE POITIERS. 12

PUISQUE de vous je n’ai autre visage,

Je

m’en vais rendre hermite en un désert, Pour prier Dieu, si un autre vous

sert,

Qu’autant

que moi en vostre honneur soit sage.

Adieu

Amour, adieu gentil corsage, Adieu ce teint, adieu ces friands yeux ; Je

n’ai pas eu de vous grand avantage :

Un

moins aimant aura peut-estre mieux13.

12 Titre

et texte donné par Pierre-François Tissot, Leçons et modèles de littérature

française ancienne et moderne. Tome second, Paris, J. L’Henry, 1836,

p. 146. Même texte donné (sans titre) par Jean-François Laharpe, Cours

de littérature ancienne et moderne. Tome 6, Paris, Ledentu et Dupont,

1826, p. 407 : « Mais de plus galant, et même de plus tendre que cette chanson

? »

13 « Que

de sentiment dans ce dernier vers ! On a depuis employé souvent la même pensée

; mais jamais elle n’a été mieux exprimée. » (Laharpe,

ibid.)

Costello’translation

TO

DIANE DE POICTIERS. 14

Puisque

de vous je n’ai autre visage, &c.

FAREWELL ! since vain is all my care, Far, in some desert

rude,

I’ll

hide my weakness, my despair ; And, midst my solitude,

I’ll

pray that, should another move thee, He may as fondly, truly love thee !

Adieu,

bright eyes, that were my heaven ! Adieu, soft cheek, where summer blooms

; Adieu, fair form, earth’s pattern given, Which love inhabits and illumes

!

Your

rays have fallen but coldly on me, One, far less fond, perchance had won

ye !

14 Louisa Stuart Costello, Specimens…,

pp. 199-200. Texte repris au moins par Lyman Abbott, The World’s Best

Poetry, Volume 3 : Sorrow and Consolation, Philadelphia, John D. Morris

and Company, 1904.

-

Henri

II, roi de France, à Diane 15

HENRI

II.

VERS

ADRESSÉS À DIANE DE POITIERS.

Plus

ferme foy ne fut oncques jurée

A nouveau

prince, ô ma belle princesse ! Que mon amour, qui vous sera sans cesse Contre

le temps et la mort asseurée.

De

fossés creux ou de tour bien murée N’a pas besoin de mon cœur la fortresse,

Dont je vous fis dame, reine et maîtresse, Parce qu’elle est d’éternelle

durée.

Trésor

ne peult sur elle estre vainqueur : Un si vil prix n’acquiert un gentil cœur.

Nous

montrons ci-après qu’Henri II n’a fait ici que copier le commencement d’un

poème de Joachim du Bellay, dont il adressera ensuite une longue version

remaniée (B.G.)

15 Pierre-René

Auguis (1786-1844), Bibliothèque des poëtes françois depuis le XIIe siècle jusqu’à Malherbe,

avec une notice historique et littéraire sur chaque poëte [6 volumes

in-8°], Paris, Renouard, Treuttel & Würtz et Lefèvre, 1824 , tome 4,

pp. 1-2 : « Henri II n’a |2 place dans notre collection

que parce qu’il avoit hérité du goût de son père pour la poésie françoise,

et qu’il a composé des vers qui annoncent un esprit cultivé ; ils sont adressés

à cette fameuse Diane de Poitiers qu’il aima si tendrement. Ces vers, écrits

de la main de Henri II, sont extraits d’un manuscrit de la Bibliothèque du

Roi, fonds de Béthune, n°8664. ».

Costello’translation

16

HENRY

THE SECOND 17,

TO

DIANE DE POICTIERS.

Plus

ferme foy.

MORE constant faith none ever swore To a new prince, oh

fairest fair !

Than

mine to thee, whom I adore, Which time nor death can e’er impair.

The

steady fortress of my heart

Seeks

not with towers secured to be, The lady of the hold thou art,

For

‘tis of firmness worthy thee : No bribes o’er thee can victory obtain,

A

heart so noble treason cannot stain !18

16 Louisa Stuart Costello, Specimens…,

pp. 207-208. Texte repris au moins par Lyman Abbott, The World’s Best

Poetry, Volume 3 : Sorrow and Consolation, Philadelphia, John D. Morris

and Company, 1904.

17 The

famous Quatrain of Nostradamus the astrologer is as follows relative to the

death of Henry the Second who was killed in a tournament

by a thrust

from the lance of Montgomery through the bars of his gilt helmet. It was

made four years before the event :

Le Lion

jeune le vieux surmontera En champ bellique par singulier duel, Dans cage

d’or les yeux lui crevera.

Deux

plaies une, puis mourir ! mort cruelle ! (Costello).

18 This

poem is sometimes attributed to Joachim du Bellay, and may be found in the

edition of his works, Rouen, 1597, among the ‘Olive de du

Bellay.’

In ‘Auguis’ ‘Poetes François,’ (Paris, 1825, 8vo.) it is given to Henry the

Second.

Plagiat

court par Henri II (Bibliothèque du Roi, fonds de Béthune, n°8664)

|

Du

Bellay 19

|

Henri

II

|

|

Plus

ferme foy ne ne fut onques jurée

A

nouveau prince, ô ma seule princesse, Que mon amour, qui vous sera

sans cesse, Contre le temps et la mort asseurée.

|

Plus

ferme foy ne fut oncques jurée

A

nouveau prince, ô ma belle princesse ! Que mon amour, qui vous sera

sans cesse Contre le temps et la mort asseurée.

|

|

De

fosse creuse, ou de tour bien murée N’a point besoing de

ma foy la fortresse, Dont je vous fy’ dame, roine, et maistresse,

Pource qu’ell’est d’eternelle durée.

|

De

fossés creux ou de tour bien murée N’a pas besoin de mon

cœur la fortresse, Dont je vous fis dame, reine et maîtresse, Parce

qu’elle est d’éternelle durée.

|

|

Thesor

ne peult sur elle estre vainqueur, Un si vil prix n’aquiert un gentil cœur

:

|

Trésor

ne peult sur elle estre vainqueur : Un si vil prix n’acquiert un gentil cœur.

|

|

Non

point faveur ou grandeur de lignage, Qui eblouist les yeulx du populaire

: Non la beauté, qui un leger courage

Peult emouvoir,

tant que vous, me peult plaire.

|

Plagiat

long

|

Du Bellay

Plus

ferme foy ne ne fut onques jurée

A nouveau

prince, ô ma seule princesse, Que mon amour, qui vous sera sans cesse, Contre

le temps et la mort asseurée.

|

Henri

II 20

Plus

ferme foy ne ne fut onques jurée A nouveau prince, ô ma seule prinsese,

Que mon amour,

quy vous sera sans cesse Contre le tems & la mort asseurée.

|

|

De fosse

creuse, ou de tour bien murée N’a point besoing de ma foy la fortresse,

Dont

je vous fy’ dame, roine, et maistresse, Pource qu’ell’est d’eternelle durée.

|

De

fose creuse, ou de tour byen murée N’a point besoing de ma foy la fortresse,

Dont je vous fy dame, roine & maystresse. Pour ce que ele est d’éternelle

durée,

|

|

Thesor

ne peult sur elle estre vainqueur, Un si vil prix n’aquiert un gentil cœur

: Non point faveur ou grandeur de lignage, Qui eblouist les yeulx du populaire

: Non la beauté, qui un leger courage Peult emouvoir, tant que vous, me

peult

|

Thrésor

ne peult sur elle estre vainqueur; Ung sy vil prix n’aquiert ung gentil cœur.

Non point faveur, ou grandeur de lignage, Quy eblouist les ieus du populaire,

Non

la beauté, quy ung léger courage Peult émouvoir, tant que vous me peult

|

19 Œuvres

françoises de Joachim Du Bellay, gentil-homme angevin, avec une notice biographique

et des notes, par Ch. Marty-Laveaux. Tome premier, Paris, Alphonse Lemerre, 1866, p. 100.

20 Georges

GUIFFREY, Diane de Poytiers, Lettres inédites, publiées

d’après

les mss de la Bibliothèque impériale, avec une introduction et des notes, Paris, Vve J. Renouard, 1866, pp. 227-229.

[plaire.

[plaire.

Mès

quy pouroyt à moy s’aconparer,

Et sy n’estyme

ryens que sa boune grâse, Et quy faroyt mon grant heur déclérer, Car otre

chose ne veut, ny ne prouchase ; Et sy ne cryns tronperye qu’on me fase,

Estant tant seur de sa gran fermeté ; Inposyble est qun otre est don ma plase,

M’ayant douné sy grande sureté.

Hellas,

mon Dyu, combyen je regrète Le tans que j’é pertu an ma jeunèse ; Conbyen

de foys je me suys souèté Avoyr Dyane pour ma seule mestrèse ; Mès je cregnoys

qu’èle, quy est déese, Ne se voulut abèser juques là

De fayre

cas de moy, quy sa[n] sela N’avoys plésyr, joye, ny contantemant Juques à

l’eure que se délybèra

Que

j’obéyse à son coumandemant.

Elle,

voyant s’aprocher mon départ,

M’a dyt

: Amy, pour m’outer de langeur, Au départyr, las ! layse moy ton ceur

Au

lyu du myen, où nul que toy n’a part.

Quant j’apersoys

mon partemant soudyn, Et que je lèse se que tant estymè,

Je

la suplye de vouloyr douner,

Pour

grant faveur, de luy béser la myn.

Et sy luy

dys ancores davantage Que la suplye de byen se souvenyr Que n’aie joye juques

au revenyr,

Tant

que je voye son hounête vysage.

Lors je

pouré dyre sertènemant

Que, moy

quy suys sûr de sa boune grâse, J’aroys grant tort prouchaser otre plase,

Car j’an resoys trop de contantemant.

-

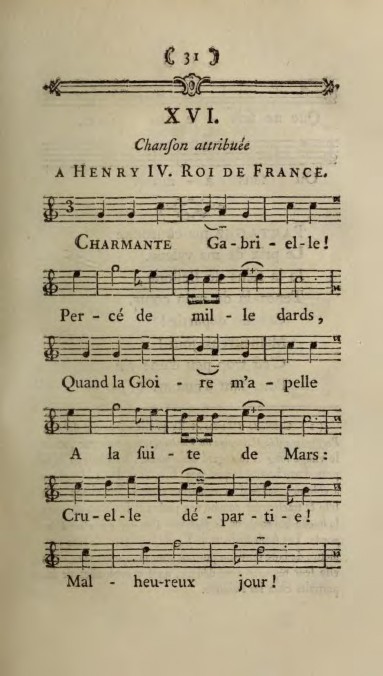

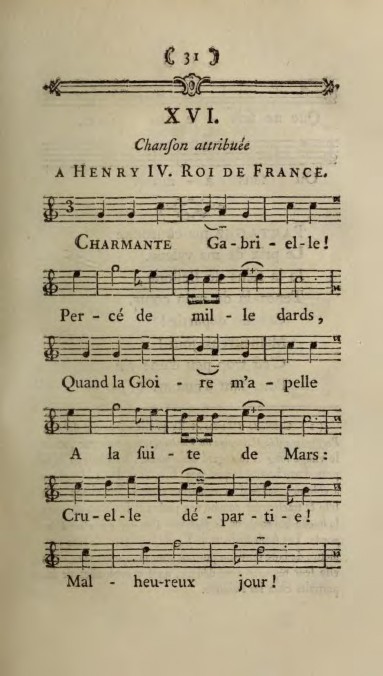

Henri

IV, à Gabrielle d’Estrée 21

CHANSON

ATTRIBUÉE À HENRI IV. ROI DE FRANCE

CHARMANTE

Gabrielle ! Percé de mille dards, Quand la Gloire m’appelle A la suite de

Mars :

Cruelle

départie ! Malheureux jour !

Que

ne suis-je sans vie, Ou sans amour.

Partagez

ma couronne Le prix de ma valeur. Je la tiens de Bellone, Tenez-la de mon

cœur.

Cruelle

départie ! Malheureux jour !

C’est

trop peu d’une vie Pour tant d’amour.

21 Jean

Monet, Anthologie franc̜ oise, ou Chansons choisies, depuis le 13e siécle

jusqu’à présent [3 volumes], Paris, Joseph-Gérard Barbou, 1765, t. 1,

pp. 31-32. Selon Yves Giraut, « Le génie chansonnier de la Nation Française

d’après l’Anthologie de Jean Monnet (1765) », in Cahiers de l’Association

internationale des études françaises 28 (1976), p. 161 ,n. 63, « Le texte

du refrain, Cruelle départie, avait été publié avec une mélodie différente

dans le Thesaurus harmonious de J. В Besard (Cologne, 1603) Charmante Gabrielle,

d’authenticité très douteuse, figure dans La Clef des Chansonniers de Ballard

(171 7) : c’est cette mélodie qui est reproduite, avec quelques ornements

ou variantes. ». Le même auteur note que Monet ne reproduit que deux couplets

sur 7.

Costello’translation

22

HENRY

THE FOURTH. SONG.23

Charmante Gabrielle !

MY charming Gabrielle!

My

heart is pierced with woe, When glory sounds her knell,

And

forth to war I go :

Parting

! — perchance our last ! Day, mark’d unblest to prove !

Oh

that my life were past, Or else my hapless love !

Bright

star, whose light I lose — Oh fatal memory !

My

grief each thought renews…

We

meet again, or die ! Parting, &c.

Oh

share and bless the crown By valour given to me,

War

made the prize my own,

My

love awards it thee ! Parting, &c.

Let

all my trumpets swell, And every echo round The words of my farewell

Repeat

with mournful sound. Parting, &c.

22 Louisa Stuart Costello, Specimens…,

p. 285.

23 Anthologie

Française, ed. de 1765 (note de Corbello). On voit

qu’elle a puisé aussi à une autre source pour ses 2e et 4e couplets.

XVIe siècle

Pierre

Baron fuit Étampes

Au

début du XIIe siècle, Étampes

chasse ses prêtres mariés dont l’un s’envole pour Oxford, y fonder une célèbre

université ; à la fin du même siècle, elle chasse ses juifs, qui s’en vont

prospérer dans d’autres contrées ; au XVIe siècle, elle chasse ses Huguenots dont l’un au moins

s’en va s’illustrer à Cambridge ; au XIXe siècle, elle ne voudra pas non plus d’ouvriers, par

crainte d’une classe ouvrière redoutée de l’aristocratie rurale ; pour finir,

Étampes est restée une ville de province d’importance constamment décroissante,

en partie parce qu’elle s’est constamment mutilée, au cours de son histoire,

de ses propres forces vives.

Nous

rééditons ici trois notices relatives à l’un de ceux qui auraient pu faire

la grandeur d’Étampes, Pierre Baron, qui fuit la persécution en cours à Étampes24, et devient professeur de Théologie à l’Université

de Cambridge, où il fera souche.

Nous

donnons donc : la notice sur Baron de La France Protestante (1877)

; celle du Dictionary of National Biography (1885) ; plus une enquête

généalogique très documentée sur sa descendance en Angleterre (1900).

24 J’éditerai

prochainement le montant du salaire perçu par le bourreau d’Étampes pour

la torture (tortura) d’hérétiques arrêtés à Méréville en 1551.

XVIe siècle

Petrus

Baro : a Huguenot from Étampes

At

the beggining of the 12th Century,

Étampes expelled its married priests, whose one flyed to Oxford, as a forerunner

of a world famous University. At the end of the same century were closed

too both the synagogue and the yeshiva of this town, and expelled all its

Jews, who flyed to others countries. During the 16th century were at heir

turn prosecuted, then expelled, the

Huguenots,

whose one became a renowned Professor of Theology at the Cambridge University.

In the 19th century also

this provincial town refused any real industrialisation for fear of the working

classes. So Etampes, which always cherished self- mutilating, remainded until

to now a charming but somewhat sleeping, rural, provincial and little town.

Thereafter

we give a reedition of three articles about Pierre Baron d’Étampes, alias

Petrus Baro Stampanus, a famed Sacrae Theologiae Doctor et

Professor in Academia Cantabrigensi, i. e. a Doctor in Theology and Professor

in the Cambridge University, ca. 1575.

-

An article about Baron from La France

Protestante (1877)

-

An other from Dictionary of National

Biography (1885)

-

And a genealogical one from The Ancestor

(1902)

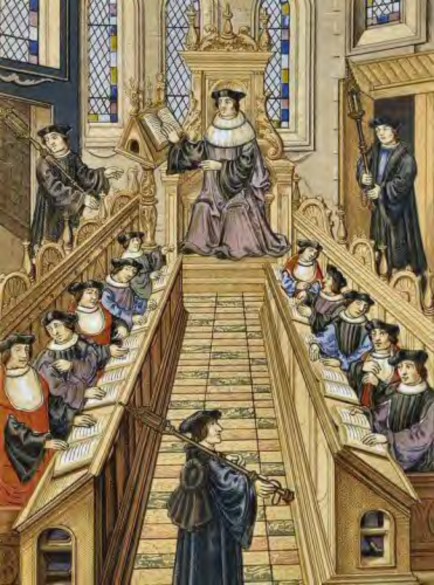

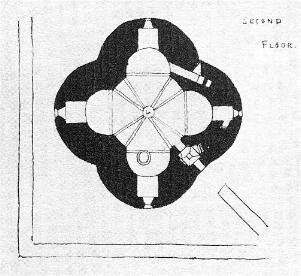

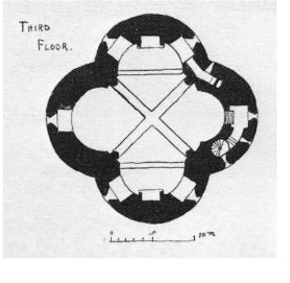

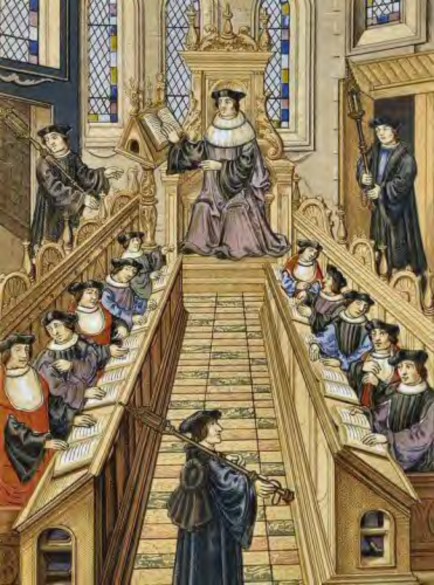

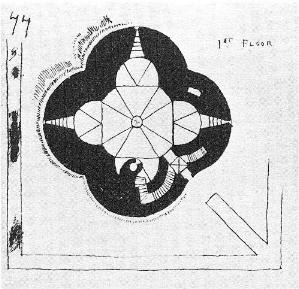

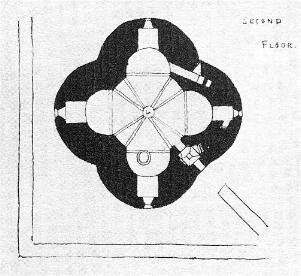

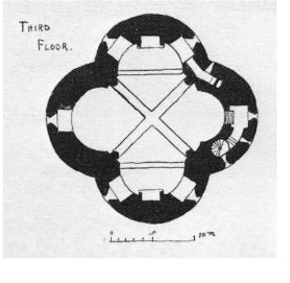

Trinity

Collège en 1575

Eugène

et Émile Haag 25

Pierre

Baron

BARON

(PIERRE) professeur à l’université de Cambridge, vers 157526. Le surnom de Stempanus qu’il prenait, indiquerait

qu’il était originaire d’Étampes. Baron fit ses études à Bourges où il prit

le grade de licencié ès lois. Chassé de sa patrie par les persécutions religieuses,

il passa en Angleterre où son mérite lui fit obtenir, quelque temps après,

une chaire dans l’université de Cambridge. Partisan des opinions pélagiennes,

il ne vécut pas longtemps en bonne intelligence avec son collègue Whitaker

qui

avait des idées plus rigides sur la prédestination. La querelle ne tarda

pas à passer de l’école dans le temple où, du haut de la chaire évangélique,

les deux adversaires |867 s’attaquèrent avec une ardeur

égale, mais avec un succès différent. Baron soutenait la thèse que Dieu n’est

point l’auteur du péché, qu’il ne veut

pas qu’on

le commette, puisqu’il le défend expressément, et que, s’il réprouve les

hommes, c’est uniquement à cause du péché qu’il hait. Il ne croyait pas non

plus à la prédestination

25 Eugène

Haag et Émile Haag, La France Protestante. Deuxième édition publiée sous

les auspices de la société de l’histoire du protestantisme français et sous

la direction de M. Henri Bordier. Tome premier, Paris, Sandoz et Fischbacher,

1877, pp. 865-867.

2626 Haag

I, 261.

absolue

; il enseignait, au contraire, que les fidèles ou les élus ne doivent point

se regarder comme assurés du salut. Cette doctrine choquait trop la majorité

du clergé anglican pour être approuvée. L’archevêque de Cantorbéry, qui voyait

ces disputes avec peine, recommanda le silence aux deux champions dans l’intérêt

de l’université ; mais Baron, ne pouvant supporter l’idée de passer pour

un hérétique aux yeux de ses élèves et des fidèles, entreprit, en 1596, de

prouver son orthodoxie dans un sermon où il s’efforça d’établir l’accord

parfait de ses opinions avec les XXXIX Articles. Il est reconnu aujourd’hui

que l’archevêque Cranmer, le principal rédacteur de ces articles dans leur

forme primitive, goûtait peu les doctrines fatalistes de Calvin, et qu’il

penchait plutôt vers le semi-pélagianisme de Luther. Dans tous les écrits

qui nous restent de lui, il se prononce en faveur de la rédemption universelle.

« Mais, dit M. Le Bas dans la Vie de l’archevêque Cranmer, dont Eug.

Haag a donné une traduction, des hommes d’un tout autre esprit ayant succédé

plus tard à nos réformateurs, la fièvre du calvinisme devant en quelque sorte

une maladie épidémique ; et vers la fin du règne d’Élisabeth, quelques-uns

de nos meneurs théologiques s’imaginèrent de parfaire nos Articles en y introduisant

une forte dose de la doctrine genevoise. » Même

dans

leur rédaction actuelle, ces Articles, surtout le XVIIe,

sont

loin

d’être favorable à la prédestination absolue. Il était donc facile à Baron

d’avoir raison contre ses adversaires, et il paraît qu’il eut effectivement

trop bien raison, car il fut cité devant le consistoire, sous l’accusation

d’avoir avancé : 1° que Dieu par une volonté absolue a créé tous les hommes

et chacun d’eux en particulier pour la |868 vie éternelle, et qu’il ne prive personne du salut,

sinon à cause de ses péchés ; 2° qu’il y a une double volonté en Dieu, une

volonté antécédente et une volonté conséquente; que par

la première Dieu ne rejette personne

puisque

autrement il réprouverait son propre ouvrage ; 3° que Jésus-Christ est mort

pour tous les hommes, proposition qu’il

appuyait

sur ce syllogisme : Christ est venu pour sauver ce qui était perdu (Mat.

XVIII, 11) ; or tous les hommes étaient perdus en Adam ; donc Jésus est venu

pour les sauver tous ; car le remède doit être de la même étendue que le

mal et Dieu ne fait point acception de personne (Act. X, 34) ; 4° que les

promesses de Dieu sont universelles, et que ce sont les hommes eux- mêmes

qui s’excluent du royaume des Cieux, selon Osée (XIV, 1). Baron n’ayant fait

aucune difficulté d’avouer ces doctrines, on dressa un procès-verbal de l’interrogatoire

et on l’envoya au chancelier qui, convaincu que toute cette procédure avait

été provoquée par des inimitiés personnelles, ne donna en conséquence aucune

suite à cette affaire. Baron continua donc à occuper sa chaire ; mais ses

ennemis se vengèrent en l’abreuvant de dégoûts, en sorte qu’à l’expiration

de ses trois années de professorat, il donna tacitement sa démission en ne

faisant aucune démarche pour conserver sa place. Il se retira à Londres où

il mourut au bout de trois ou quatre ans. Il laissa plusieurs enfants, dont

l’aîné seul, nommé SAMUEL, est mentionné particulièrement ; encore les biographes

se bornent- ils à nous apprendre qu’il exerça la médecine et mourut à Lyn-

Regis dans le Norfolkshire. Les ouvrages de Baron pourraient, encore de nos

jours, offrir de l’intérêt, les questions qui y sont traitées continuant

à être agitées dans l’Église; malheureusement ils sont fort rares. Nous en

donnerons le catalogue d’après Watt.

-

Quatre sermons sur le Ps. CXXIII,

Lond., 1560, in-8°.

-

In

Jonam prophetam prælectiones XXXIX27 ; — Theses

publicæ in scholis peroratæ et disputatæ28 ; — Conciones tres

27 « Trente-neuf

leçons relatives au livre du prophète Jonas » (B.G.).

28 « Thèses

défendues publiquement sour une forme oratoire et contradictoire » (B. G.)

ad

clerum catibrigiensis habitæ in templo Beatæ Mariæ29 ; — Precationes quibus usus est

author in suis prælectionibus |869 inchoendis et finiendis, Lond. 1579, in-fol. — Les thèses ont été trad. en angl. par

Ludham et publiées, la 1re sous le titre :

«

God’s purpose and decree taketh not away the liberty of man’s corrupt will

; » la 2e sous celui-ci

: « Our conjonction with Christ is altogether spiritual, » Lond. 1590, in-8°.

-

De

fide, ejusque ortu et naturâ, plana et dilucida explicatio30, Lond., 1580, in-8°. — La Biblioth. Telleriana mentionne cet

ouvrage, mais sous un titre un peu différent: Explicatio

de fide, ejusque ortu et naturâ, et alia opuscula theologica31, Lond., 1580, in-4°. Mais il n’est pas probable qu’il y en ait

eu deux éditions dans la même année.

-

Summa

trium sententiarum de prædestinatione32, imp.

Avec des Notes de J. Piscator, une Disquisitio de F. Junius

et une Prælectio de Whitaker; Hard., 1643, in-8°.

-

Special Treatise of God’s Providence, and of comforts against all kinds of crosses and calamities

to be fetched from the same; with an Exposition on Ps. CVII.

-

Sermones

declamati coram almâ universitate cantibrigiensi33, Lond.,

in-4°, sans date.

29 « Prières

dont use l’auteur pour commencer et conclure ses leçons » (B. G.)

30 « Exposé

clair et limpide sur la foi, son origine et sa nature » (B. G.).

31 « Exposé

sur la foi, son origine et sa nature et autres opuscules théologiques » (B.

G.).

32 « Résumé

de trois déclarations au sujet de la prédestination » (B. G.).

33 Discours

tenus devant la très maternelle université de Cambridge.

-

De præstantiâ et dignitate divinæ

legis libri duo, in quibus varii de lege errores refelluntur,

et quomodò lex gratuitum Dei cum hominibus fœdus ac Christum etiam ipsum

comprehendat, fidemque justificantem à nobis requirat, explicatur ; eaque

doctrina sacrarum literarum authoritate theologorumque veterum ac recentiorum

testimoniis confirmatur ; adjectus est alius quidam Tractatus ejusdem authoris

in quo docet expetitionem oblati à mente boni, et

fiduciam

ad fidei justificantis naturam pertinere34, Lond., in-8°

sans date.

34 Ouvrage

en deux parties sur l’excellence et la dignité de la Loi divine, dans lequel

on réfute différentes erreurs au sujet de la Loi, où on explique comment

elle contient le pacte gracieux de Dieu avec les hommes, ainsi que le Christ

lui-même, et où on prouve cette doctrine par l’autorité des sainte Écritures

et les témoignages des théologiens anciens et modernes. On y a joint un certain

autre traité du même auteur dans lequel il enseigne

Un

cours à l'Université de Paris au XVIe siècle

James

Bass Mullinger 35

Peter Baro

(1534-1599)

BARO,

PETER (1534–1599), controversialist, son of Stephen Baro and Philippa Petit,

his wife, was a native of France, having been born December 1534 at Etampes,

an ancient town between Paris and Orleans. Being destined for the study of

the civil law, he entered at the university of Bourges, where he took his

degree as bachelor in the faculty of civil law 9 April 1556. In the following

year he was admitted and sworn an advocate in the court of the parliament

of Paris. The doctrines of the reformers were at this time making rapid

progress in France, and Bourges was one of their principal centres. Here,

probably, Baro acquired those doctrinal views which led him shortly after

to abandon law for divinity. In December 1560 he repaired to Geneva, and

was there admitted to the ministry by Calvin himself. Returning to

France he married, at Gien (on the Loire), Guillemette, the daughter of

Stephen Bourgoin, and Lopsa Dozival, his wife. The ‘troubles in

France,’ Baro tells us (whether prior to or after the massacre of St.

Bartholomew does not appear), now induced him to flee to England, where he

was befriended by Burghley, who admitted him to dine at his table, and, being

chancellor of the university of Cambridge, exercised his influence on Baro’s

behalf with that body. (The foregoing facts are derived from a manuscript

in Baro’s own handwriting, transcribed in Baker MSS. xxix. 184-8.)

He was admitted a

35 Dictionary

of National Biography, Volume 3 : Baker-Beadon,

London, Smith, Elder and Co, 1885, pp. 265-267.

member

of Trinity College, where Whitgift was then master. The provost of King’s

College, Dr. Goad, engaged him to read lectures in divinity and Hebrew. In

1574, through the influence mainly of Burghley and Dr. Perne, he was chosen

Lady Margaret professor of divinity. On 3 Feb. 1575-6 he was incorporated

in the degrees of bachelor and licentiate of civil law, which he had taken

at Bourges. In 1576 he was created D.D., and was incorporated in the same

degree at Oxford on 11 July. His stipend as professor was only 20l.

a year, and on 18 March 1579 the university recommended his case through

the deputy public orator to the state secretaries, Walsingham and Wilson,

for their consideration in the distribution of patronage, but apparently

without result.

Notwithstanding

his connection with Geneva, Baro appears to have gradually become averse

to the narrow doctrines of the reformed or Calvinistic party, and a series

of complaints preferred against him in 1581 show that he was already inclining

to Arminianism, and was prepared to advocate something like tolerance even

of the tenets of Rome. Between Laurence Chaderton (afterwards master of Emmanuel

College at Cambridge) and himself there arose a somewhat sharp controversy;

and by Chaderton’s biographer (Dillingham) Baro is accused of having brought

‘new doctrines’ into England, and

of

publishing them in his printed works36. The controversy

was amicably settled for the time; but it was again revived by the

promulgation

of the Lambeth Articles in 1595. These articles, which were chiefly the work

of William Whitaker, the master of St. John’s and the most distinguished

English theologian of his day, and Humphry Tyndal, acting in conjunction

with Whitgift, had undoubtedly their origin in the design to repress all

further manifestations of anti-Calvinistic views, such as

36 Vita

Laurentii Chadertoni, pp. 16-7.

those on which Baro and others had recently ventured.

Whitgift, writing to Dr. Neville (his successor at Trinity College) in December

1595, says: ‘You may also signify to Dr. Baro that her majesty is greatly

offended with him, for that he, being a stranger and so well used, dare presume

to stir up or maintain any controversy in that place of what nature soever.

And therefore advise him from me utterly to forbear to deal therein hereafter.

I have done my endeavour to satisfy her majesty concerning him, but

how it will fall out in the end I know not. Non decet hominem peregrinum

curiosum esse in aliena

republica’37. It is possible that, owing to the intervention of the

Christmas

vacation, this warning reached Baro too late. On 12 Jan. following he preached

before the university at Great St. Mary’s, and ventured to criticise the

Lambeth Articles. His long labours as a scholar and his position as a professor

entitled him to speak with some authority. At the same time his observations

do not appear to have been conceived in any captious spirit, but rather with

the design of justifying his formal acceptance of the new articles, and explaining

the construction which he placed upon them. The Calvinistic party, flushed

with their recent victory, were, however, incensed at his presumption; for

his discourse was construed into an attempt to reopen a controversy which

they fondly hoped had been set at rest for ever. Although but few of the

heads were in Cambridge, the vice-chancellor, Roger Goad, felt himself under

the necessity, after a consultation with one or two of their number, of communicating

with Whitgift concerning ‘this breach of the peace of the university.’ Baro

himself deemed it expedient to defend his conduct in a letter to the archbishop,

and to seek a personal interview with him. His efforts were, however, without

result. Whitgift looked upon his ‘troublesome course of contending’ as inexcusable,

while he was himself too definitely pledged to the

defence of the new articles to be able to entertain any

proposition which involved their reconsideration or modification. Baro was

cited before the vice-chancellor and heads, and required to produce the manuscript

of his sermon, while he was peremptorily forbidden to enter upon further

discussion of the doctrine involved in the Lambeth Articles. It is probable

that the proceedings would have resulted in his actual removal from his professorial

chair had it not become apparent that he was not without sympathisers and

friends. Burghley interposed in his behalf with unwonted vigour, expressing

his opinion that the professor had been too severely dealt with; while Overall

(afterwards bishop of Norwich), Harsnet (afterwards archbishop of York),

and the eminent Lancelot Andrewes, all alike declined to affirm that the

views which he had put forth were heterodox. The election to the Lady Margaret

professorship was, however, at that period a biennial one, and Baro’s

appointment terminated November 1596. Before that time, foreseeing that

he would probably not be re-elected, he wrote to Burghley, offering, if continued

in office, to treat of the doctrine of predestination with great caution,

or even altogether to abstain from any reference to it. His appeal was not

attended with success, and before the year closed he deemed it necessary

to leave Cambridge. ‘Fugio, ne fugarer,’ the utterance attributed to him

on the occasion, sufficiently indicates the moral compulsion under which

he

acted.

Dr. John Jegon, the master of Corpus Christi College, made an effort to bring

about his return. Writing to Burghley38 he speaks of Baro as one who ‘hath been here longe time a painful

teacher of Hebrew and divinity to myself and others,’ and ‘to whome I am

very willing to showe my thankful minde;’

and

he then proceeds to suggest that should Baro return ‘and please to take

pains in reading Hebrew lectures in private

houses,

I doubt not but to his good credit, there may be raised as great a stipend’39.

Baro

did not, however, return to Cambridge, but lived for the remainder of his

life in London; residing, according to the statement of his grandson, ‘in

a house in Dyer’s Yard, in Crutched Fryers Street, over against St. Olive’s

Church, in which he was buried’40. He died in April 1599,

and Bancroft, at that time bishop of London, who sympathised with him both

in his views and in the treatment he had experienced, honoured him with an

imposing funeral, in which the pall was borne by

six

doctors of divinity, and the procession (by the bishop’s orders) included

all the clergy of the city. The feature which invests Baro’s career with

its chief importance is the fact that he was almost the first divine in England,

holding an authoritative position, who ventured to combat the endeavour to

impart to the creed of the church of England a definitely ultra-Calvinistic

character, and he thus takes rank as the leader in the counter movement which,

under Bancroft, Andrewes, Laud, and other divines, gained such ascendency

in the church of England in the first half of the following century. Writing

to Nicholas Heming,

the

Danish theologian, from Cambridge41, he says: ‘In this

country we have hitherto been permitted to hold the same

sentiments

as yours on grace; but we are now scarcely allowed publicly to teach our

own opinions on that subject, much less to publish them’42. Some twenty years later, it being asked at court what the Arminians

held, the reply was made that they held all the best bishoprics and deaneries

in England.

39 MASTERS, Life of Baker, p. 130.

40 Baker

MSS. xxix. 187.

41 1 April

1596.

42 ARMINIUS, Works, ed. Nichols, i. 92.

Baro

had eight children, most of whom died young. The eldest, Peter, was a doctor

of medicine, and, with Mary, his wife, was naturalised by statute 4 Jac.

I. He practised at Boston in Lincolnshire, where he successfully exerted

himself to uphold Arminian views43. A grandson, Samuel

Baron, practised as a physician at Lynn Regis in Norfolk, and had a large

family; his fifth son, Andrew, was elected a fellow of Peterhouse in

1664.

Baro’s principal published writings were: 1. ‘Praelectiones’ on the Prophet

Jonas, edited by Osmund Lake, of King’s College, London, fol. 1579; this

volume also contains ‘Conciones ad Clerum’ and ‘Theses’ maintained in the

public schools. 2. ‘De Fide ejusque Ortu et Natura plana ac dilucida Explicatio,’

also edited by Osmund Lake, and by him dedicated to Sir Francis Walsingham,

London, 8vo, 1580. 3. ‘De Praestantia et Dignitate Divinae Legis libri duo,’

London, 8vo,

n.

d. 4. ‘A speciall Treatise of God’s Prouidence,’ &c., together with certain

sermons ad clerum and ‘Quaestiones’ disputed in the schools; englished by

I. L. (John Ludham), vicar of Wethersfielde, London, 8vo, n. d. and 1590.

5. ‘Summa Trium de Praedestinatione Sententiarum,’ with notes, &c., by

John Piscator, Francis Junius, and William Whitaker, Hardrov. 12mo, 161344. His ‘Orthodox Explanation’

of the Lambeth Articles45 is

printed in Strype’s ‘Whitgift,’ App. 201.

[The account

of Baro’s early life, in his own handwriting, was found in the study of his

great grandson at Peterhouse after the death of the latter; it was transcribed

by Baker (MSS. xxix. 184-8), and abridged in Masters’s Life of Baker, pp.

127-30. See Mayor’s Catalogue of Baker MSS. in the University Library, Cambridge,

p. 301; Cooper’s Athenae Cantab. ii. 274-8; Mullinger’s Hist. of the

43 COTTON MATHER, Hist. of New

England, bk. iii. p. 16.

44 reprinted

in ‘Praestantium ac Eruditorum Virorum Epistolae Ecclesiasticae et Theologicae,’

1704.

45 A translation

of the Latin original in Trin. Coll. Lib. Camb., B. 14, 9.

University

of Cambridge, ii. 347-50; Cotton Mather’s Hist. of New England; Whitgift’s

Works (by Parker Society, see Index); Strype’s Life of Whitgift and Annals

of the Reformation; Heywood and Wright’s Cambridge Transactions during the

Puritan Period, ii. 89- 100; Nichols’s Life and Works of Arminius, vol. i.;

Haag’s La France Protestante, 1st ed. i. 261 seq., 2nd ed. i. 866 seqq.]

J. B. M.

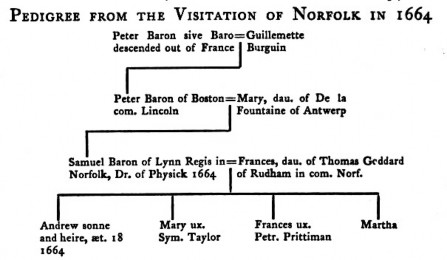

A

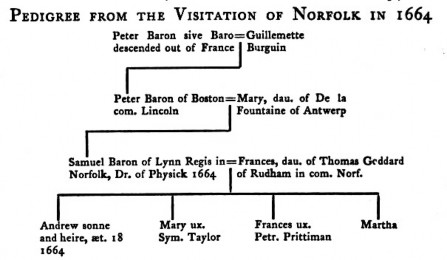

HUGUENOT FAMILY IN ENGLAND

THE

BARONS 46

SIDE

by side with such Huguenot families as the Tryons, rich merchants whose necks

and money bags were alike endangered by their profession of ‘the religion’

– came other emigrants fleeing a more imminent danger. These were the ministers

of the reformed Churches, of whom many took refuge in England with their

families, soon Englishing themselves in speech and habit, and adding a new

note to that chorus of religious controversy which was as the breath of the

nostrils to English scholars of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Of

such were the Barons, a family for four generations settled in Cambridge,

Lincolnshire and Norfolk.

Pierre

Baron, or Petrus Baro, as he wrote himself after the fashion of the continental

theologians of his day, the founder of this family in England, was a scholar

and divine of some note in his day ; for this foreign graft in the English

Church may claim ancestorship of the great High Church party of the seventeenth

46 Unknown

Author, « The Huguenot families in England. II. The Barons », in The Ancestor,

a quarterly review of county and family history, heraldry and antiquities

3 (october 1902), pp. 105-117.

century,

whose service to England was to save her from the claws of Calvinism.

From

a collection of family papers which Cole the antiquary transcribed from a

MS. under the hand of Thomas Baker we learn much of the early history of

the famous Petrus47. He was the son of Estienne Baron

of Etampes near Orleans, by Philippe Petit his wife, and was one of many

children of whom the names are preserved of Jehan Baron and Florent Baron,

both apparently elder brothers of Pierre.

The

family seems to have been one of the rich bourgeoisie or petite noblesse.

Peter Baron, who was possibly a nephew of our theologian, is remarkable as

having at a great age defended Etampes during a siege, to which siege he

himself gave that measure of immortality which a long epic poem in Latin

– Stempanum48 Halosis – can assure.

With Pierre Baron the theologian let our genealogy begin.

-

PIERRE BARON,

born about 1534 at Etampes, was bred

|106 a

scholar, taking his degrees of bachelor and licentiate or civil law at Bourges49, which town was then

the headquarters of the reformed doctrine in France. In 1557 he was received

as an advocate in the parliament court at Paris. ‘Afterwards, being aged

26 years, the year and month in which Francis II. King of France, died at

Orleans, that is to say the year 1560, in December, he withdrew himself to

Geneva and there, having given himself to the study of theology, was made

minister and

47 British

Museum Add. MS. 5832.

48 In

fact Stemparum Halosis (B.G. 2014)

49 9 and

10 April, 1555 (Cole’s MS.).

received

the imposition of hands from Jean Calvin’50. At some

date between the 17 May and 7 June 1563 he was married at Gien on the Loire

to Guillemette Burgoin daughter of Estienne Burgoin, a merchant, by Lopza

Dozival his wife. Her brothers, François Burgoin and Antoine Burgoin, are

named amongst the godparents of their sister’s children. Coming to England

with his family he was befriended by the Lord Burghley, who was at that time

Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge received the foreign

scholar under its Chancellor’s

protection,

and on 3 Feb. 1575/6 51 he was

incorporated in those degrees in law which he had taken at Bourges. In 1576

he

received

the degree of Doctor of Divinity, and on 11 July of that year he was incorporated

in the same degree at Oxford. On the 18 March 1578/9 his university recommended

his case to the Secretaries of State, and he was preferred to the Lady Margaret

Professorship of Hebrew. The active mind of Baron did not long allow itself

to enjoy its newly gotten freedom in quiet content. His earlier experiences

of Calvinism, coloured as they were by personal knowledge of both Calvin

and Beza, had turned the bent of his mind against that system which was then

in Baron’s early days at Cambridge so eagerly studied by his fellows. In

1581 he was already reckoned as one inclined to Arminianism, and was indeed

suspect of another heresy – the loathed doctrine of tolerance for the religious

beliefs of others, a tolerance which Dr. Baron would have extended, as it

was believed, to the beliefs of those who had hunted him from his native

land. His sallies into controversy was very ill received by his adopted countrymen,

and he was soon risking that Tudor wrath which might readily have proved

as unwholesome for a theologian as the zeal of any inquisitor. In December

of 1595

50 Coles

MS.

51 Comprenez

1575 ancien style (avant Pâques), 1576 nouveau style (B.G 2014).

Whitgift

wrote that Dr. Baro had |107 greatly offended her Majesty

‘that he, being a stranger and so well used, should dare to stir up or maintain

any controversy in that place of what nature soever – Non decet hominem

peregrinum curiosum esse in aliena republica.’52

The

plain words of warning came too late to save Doctor Baro at Cambridge. On

12 Jan. 1595/6 he preached before the University at Great St. Mary’s, criticizing

those Lambeth Articles which Whitaker, Tyndal and Whitgift had drawn up for

the repression of anti-Calvinism. It was in vain for Doctor Baro to protest

that he formally accepted those articles, for the controversialist allowed

himselr to explain his construction of them. In the November of 1596 his

term as Lady Margaret Professor ended and it was not renewed, although he

offered, if re-elected, to be cautious in his words concerning predestination,

or, better still, to leave that vexed question alone for the future. To the

High Calvinist this refusal of battle at the crossways had something in it

of insult. Calvinism would not accept toleration, and although Burghley stood

by Dr. Baro, and Harsnet, the northern archbishop, and Lancelot Andrewes,

Cambridge

would not hold the ex-Lady Margaret Professor. ‘Fugio,’ he said, ‘ne

fugarer’53 and for the second time in

his life Doctor Baro fled the storm. The rest of his years were spent in

London at a house in Dyers Yard, Crutched Friars, in the parish of St.Olave’s

in Hart Street. There under the altar of the

parish

church he was buried, Bancroft the Bishop of London commanding the attendance

of all his parish clergy at the funeral, at which Doctors of Divinity

walked as pall-bearers.

52 Whitgift’s

Works, iii. 617. – « Il ne convient pas à un résident étranger d’être trop

entreprenant dans une communauté qui n’est pas la sienne » (B.G.).

53 « Je

fuis pour ne pas être mis en fuite » (B.G.).

Twenty

years later all the best bishoprics and deaneries were filled by the supporters

of those tenets for which Dr. Petrus Baro had been hunted from Cambridge.

He

left a will dated in March 1598, written in the Latin which was for a mother

tongue to the wandering scholars and divines of his day. Petrus Baro –

he describes himself therein – juris primum civilis licentiatus deinde

theologie professor, Gallus Stempanus – a Frenchman of Etampes – nunc

Londini in Anglia degens, annos natus sexaginta quatuor, et bona nihilominus

firma memoria judicioque dei gratia sano54.

By this will he gave ten shillings to Margaret, formerly his maid, who lived

at

Cambridge.

He gave to his two twin daughters, Elizabeth and Katherine, 100 l. each if

they were unmarried at his death. |108

The

residue of his goods in England or in France he gave amongst his children

Peter, Andrew, Martha, Mary, Elizabeth and Katherine. He made his sons Peter

and Andrew his executors, who proved the will 27 April 159955.

By

his wife Guillemette Burgoin, who died before him, Petrus Baro left issue

:

-

Peter Baron of Boston in Lincolnshire,

esquire, of whom hereafter.

-

Estienne Baron, born at Orleans 4 Nov.

1567, and christened there the same day. He died 4 Feb. 1568.

-

Estienne Baron, born at Sancerre 10 Oct.

1568. He was christened the same day and died on the morrow.

-

Andrew Baron of Boston in Lincolnshire,

gentleman. He was born at Cambridge 8 July 1574, and was christened there

54 « Pierre

Baron tout d’abord licencié en droit civil puis professeur de théologe, français,

étampois, à présent résident à Londres en Angleterre, âgé de soixante-quatre

ans et cependant encore doté grâce à Dieu d’une bonne et ferme mémoire et

sain d’esprit » (B.G.)

55 P.C.C.

28 Kidd.

the

following Sunday. He was buried at Boston 25 May 1658. His will is dated

1 August 1653. He gave to Andrew Slee (his grandson) all his lands and tenements,

save his house in Gaunt Lane, with remainder, should the said Andrew die

without issue to George Slee (another grandchild), with certain exceptions

in favour or Hester Slee (another grandchild) and Mary Slee. To his daughter

Mary Houbelon, if a widow, he gave the dwelling house dwelled in by Master

Bedford. To his nephew Doctor (Samuel) Baron, to Mary Houblon, to Anne Slee

and to Margaret Slee he gave small legacies in money, and the residue of

his goods, with the house in Gaunt Lane, which was probably his own dwelling

house, he gave to his son (in law) George Slee. Administration with this

will annexed was granted

29

Nov. 165856 to the said George

Slee, the residuary legatee.

Andrew

Baron’s wife’s name was Hester. She was buried at Boston 1 April 1639. By

her he had issue :

-

Hester Baron, who was married at

Boston 25 Sep. 1628 to George Slee of Boston and Algarkirk, gent. He was

born about 1607, being aged 33 in 15 Car. I., when he was a deponent in the

suit which Peter Baron (his wife’s first cousin once removed) brought |109 by

his guardian against Newdigate Poyntz and others57,

Hester Slee was buried at Boston 17 August 1637. George Slee remarried with

Mary (probably dau. of Daniel Houbelon, who was buried at Boston 2 Jan. 1639/40).

She was buried at Boston 15 August 1662. The will of George Slee of Algarlcirk

was dated 4 Nov. 1675, an proved 2 May

56 P.C.C.

614 Wootton.

57 Chan.

pro. before 1714, Mitford 599.

167758 by his son Andrew Slee, the exor. George

Slee had issue

(1)

Andrew

Slee of

Boston, esquire, M.D., who married about Feb. 1658, Joan Smith, daughter

of Edward Smith of the city of Lincoln, gent., who died before him and was

buried at Boston 5 Nov. 1660, leaving issue by both her husbands. On 5 May

1666

Andrew

Slee answered the Chancery bill set forward by the guardian of Samuel Baron

of Horncastle, son of the said Joan59.

Andrew Slee made a will 31 May 1678, which was proved 2 Aug. 167860 by Israel Jackson, John Boult, Samuel

Hutchinson and Richard Palfreyman, gentlemen, the exors. (2) George Slee

of Boston, gentleman, born about 1633, whose will was dated 20 Nov. 28 Car.

II., admon. with the will being granted 13 Feb. 1676 to his brother Andrew,

uncle and guardian of Meriam and Elizabeth the children, whose mother Frances

was dead without proving the will in which she had been named as extrix.

The

said Frances,

born about 1646, was daughter of one Pepper of Boston, and was married with

her mother’s consent to George Slee by license from the Bishop of Lincoln,

dated 11 March 1667/8. (3) Hester Slee, named in her father’s will as wife

of Mr. Thomas Stowe. (4) Mary Slee, named in her father’s will as wife of

Henry Calverley, by whom she had issue. And (5) Elizabeth Slee (evidently

a daughter |110 by the second marriage), to whom her father gave

‘the pictures of her

grandfather

Houbelon and grandmothers, with that of her uncle Houbelon and her mother’s.’

-

Mary Baron, who was christened at

Boston 19 March 1608/9. ‘Mary Baron, daughter of Andrew Baron, gent.,’ was

58 Cons.

Linc.

59 Chan.

pro. before 1714, Collins 30.

60 Cons.

Linc.

buried

at Boston 7 March 1637/8. But in his will of 1653 Andrew Baron bequeathed

a house to his ‘daughter Mary Houbelon, if she be a widow.’ The position

of this second Mary in the pedigrees of Baron and Houblon has not yet been

ascertained.

-

Hester Baron, christened at Boston

20 March, 1612/3. She probably died young.

(iD.)

Martha Baron, eldest daughter of Peter and Guillemette Baron. She was born

at Orleans 1 June 1564.

(iiD.) Marie

Baron, born at Sancerre 26 May [1570 ?].

(iiiD.)

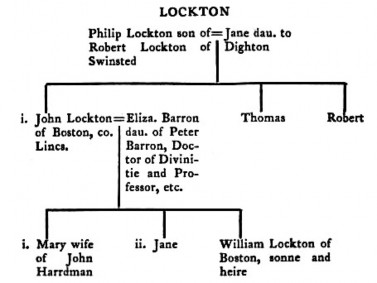

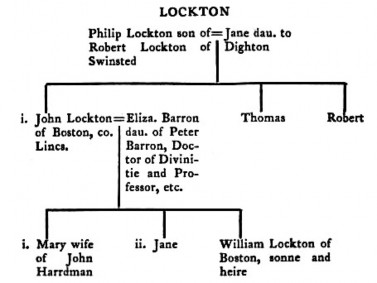

Elizabeth Baron, born at Cambridge 24 Aug. 1577, and christened there the

Tuesday following. She married John Lockton of Boston, gent., by license

from the Bishop of Lincoln, dated 28 May 1600. He was son of Philip Lockton,

a son of Lockton of Swinstead, and left issue by his wife.

(ivD.)

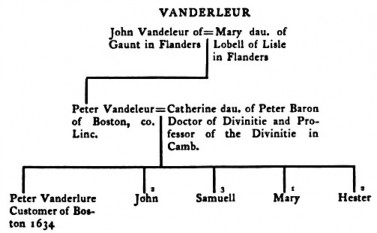

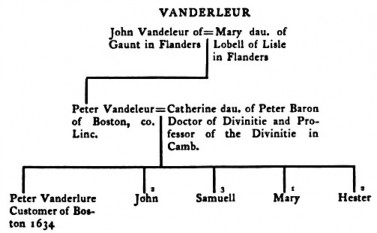

Catharine Baron, born 24 Aug. 1577, twin with Elizabeth. She married Peter

Vandeleur or Van der Leur of Boston, a refugee from Ghent in Flanders, by

whom she had issue. He was buried at Boston 24 Sep. 1638.

-

PETER BARON of Boston in Lincolnshire,

esquire, was born at Orleans 15 Jan. I566/7, and coming to England with his

father was naturalized by statute of 4 Jac. I. The register of Peterhouse

at Cambridge for 1585 records that he was ‘admissus coram sociis,’ he signing

the register with his own hand, per me Petrum Baro Aureliensem. He

was a doctor of medicine, and under the Cecil influence was made

free of

Boston

25 Oct. 1606, becoming alderman in 1609 and mayor in 1610. The author of

The Way of Congregational Churches Cleared (ed. London, 1648)

thus speaks of him :

When

I was first called to Boston in Lincolnshire [1612] so it was that Mr. Doctor

Baron, son of that Doctor Baron (the Divinity |111 Reader at Cambridge, who in his lectures there first

broached that which was then called Lutheranism, since Arminianism). This

Doctor Baron, I say, had leavened many of

the

chief men of the town with Arminianism, as being himself learned, acute,

plausible in discourse, and fit to insinuate into the hearts of his neighbours.

And though he was a physician by profession (and of good skill in that art)

yet he spent the greatest strength of his studies in clearing and promoting

the Arminian tenets.

He

lived in a mansion house, formerly of the Westlands, which stood between

the east end of Beadman’s Lane and Spain Lane in Boston, which was afterwards

held by his great nephew Andrew Slee. He died 6 Sep. 1630 and was buried

at Boston 7 Sep. 1630, the entry in the register describing him as a justice

of the peace and doctor of physic. By inquest post mortem taken at

Boston 2 July 8 Car. I. it was returned that he died seised of lands in Conisby,

Sibsey, Skirbecke, Wyberton, Kirton, Moulton and Leake. He made a will 31

May 1628 describing himself therein as ‘Peter Baron alias Baro of

Boston in the county of Lincoln esquier and doctor of Phisick,’ the only

legatees being his elder son Peter Baron, who had lately married Martha Forrest,

daughter of Myles Forrest of Peterborough, esquire, and his younger son Samuel

Baron. The testator’s wife Mary was then lately dead. The will was proved

22

Feb. 1630/161 by Peter Baron

the son and exor. Admon.

61 P.C.C.

25 St. John.

-

was granted

29 Dec. 1664 to Samuel Baron, brother of the exor., who was then also dead.

Peter Baron married Mary, who is described in the Heralds’ Visitation of

Norfolk in 1664 as a daughter of De la Fontaine of Antwerp. She died in April,

1628, and was buried at Boston 26 April 1628.

Peter Baron

and Mary de la Fontaine had issue : –

-

Peter Baron of Boston, esquire,

of whom hereafter,

-

Samuel Baron of South Lynn in

Norfolk, gent. As ‘Samuel Baron Lincolinensem’ he was admitted to Peterhouse

in Cambridge. Like his father he was a Doctor of Physick and settled at South

Lynn in Norfolk, where his father had owned a house. He died 12 April 1673,

and was buried 15 Ap. 1673 at South Lynn as ‘Samuel Baron esquire.’ A marble

stone at the foot of the altar in All Saints’ Church in South Lynn marked

his grave. He made a will 10 Aug. 1671, with a codicil dated 24

Jan.

1672/3 which was proved 26 May 167362 by Andrew |112

Baron

the son and exor. He gave his lease of the rectory of Sharnborne, co. Norfolk,

to his daughter Martha Baron, with 800 l. He gave the ultimate reversion

of his house and lands in South Lynn, and in Algarkirk, Fossdyke, Freeston

and Butterwick in Lincolnshire, with the manor of Roos Hall, to his son Andrew

Baron. He married 15 Feb. 1630/1. Frances Goddard, the only daughter of Thomas

Goddard of Stanhow and Rudham in Norfolk, esquire. She died 19 June 1667,

and was buried 21 June 1667, at South Lynn, where a marble slab near that

of her husband marks her grave. Upon it are the arms of Baron impaled with

an eagle for Goddard.

Samuel Baron

and Frances Goddard had issue –

-

Samuel

Baron, born 10 Dec. 1633, who died young before 1664.

-

Thomas Baron, born 1 Feb.

1646/7, who died young before 1664.

-

Peter Baron, born I Jan.

1636/7, who died young before 1664.

-

Andrew Baron of South Lynn

and Cambridge. He was born 18 June 1645, and was returned as his father’s

son and heir in the Heralds’ Visitation of Norfolk in 1664. He was of Peterhouse,

Cambridge, a bachelor of arts 20 May, 1664/5 and fellow of his college 24

May 1666, M.A. March 1667/8. He

died

14 Aug. 1719, aged 74. His will, dated 2 Sep. 1709, was proved 6 Oct. 171963 by Samuel Taylor of Lynn, merchant,

one of the exors. He was buried 17 Aug. 1719, at South Lynn as ‘Mr. Andrew

Baron the impropriator,’ and lies in the chancel near his father and mother

under a stone bearing the arms of

Baron.

It is

probable that the descendants in the male line of Petrus Baro ended with

this Andrew Baron, his great-grandson.

-

Samuel Baron, born 16 July

1646, dead before 1664.

-

Henry Baron, born on Lammas